Paul Broman: When Science Outgrew Religion--The Decline of Natural Theology--Part 2--Science Touches the Mysteries of Creation

Guest essay on Wednesday, 26 June 2024

We heard Paul Broman give a wonderful lecture at the Atlanta Freethought Society a week or two back and I was so impressed that I asked him to allow me to use it as a guest essay—in fact three of them (today’s is the second). He graciously agreed.

I learned some new things—and you may, too. And I was delighted with the review of some things I already knew, too—I hope the same happens to you.

Thanks, Paul!

When Science Outgrew Religion

by Paul Broman

Academic disclaimer

The author of these essays (Parts 1-2-3), Atlanta Freethought Society member Paul Broman, is not a credentialed historian. He does have a college degree, but not in the Humanities. Paul is, however, an avid history buff who is well read in non-fiction titles, especially science histories. Paul has made every effort to ensure that all the information contained in this essay is historically accurate but has not read every book mentioned in this essay, and has relied on academic summaries of those works.

Part 2: Science Touches the Mysteries of Creation

Fossils had been observed since ancient times, and there had been debate going back to antiquity about whether fossils were natural formations which “grew within rock,” remains of mythical creatures, remains of ordinary creatures, or some combination thereof.

Greek historian Herodotos thought that fossil skulls which had been found in Greece were remains of mythical creatures like the Cyclops or Griffin. The skulls of elephants have a large hole where the trunk enters, which the ancients mis-interpreted as a single large eye socket.

Greek philosopher Xenophanes might have been the first person to argue that at least some fossils were remains of living things (in the case of fossilized sea shells).

The highly influential Platonic Greek philosopher Aristotle believed fish fossils he encountered were evidence that certain kinds of fish live in the ground and can be only found by digging.

In the year 77 C.E. Roman philosopher Pliny the Elder wrote about fossils in his epic work Natural History, but did not understand their significance. He mis-identified fossil "tongue stones”, which he called glossopetrae, which he suggested fell from the sky during lunar eclipses. He gave a name to ammonite fossils, which he called “Horns of Ammon”, and thought were magical relics related to the Egyptian god Ammon-Ra. He also described ”toadstones,” which were thought until the 18th century to be a magical cure for poison originating in the heads of toads, but which are actually fossil teeth from an extinct fish.

Fossils would continue to be just a curiosity with no further naturalistic investigation for over a millennia after the end of antiquity. Leonardo Da Vinci made the first recorded insightful studies of fossils after antiquity, recording ideas and drawings in personal journals that might have set the science of geology forward hundreds of years if they had not been forgotten after his death. His work with fossils was not re-discovered until the 19th century, after the insights he had in the 16th century had already been made by others.

The science of geology would not really get started until 1667, when Danish naturalist (and later, Catholic priest) Nicholas Steno realized while dissecting a shark that Pliny’s mysterious “tongue stones” were, in fact, simply shark teeth in rock. Steno was inspired by his shark tooth discovery to undertake serious investigation into fossils, and after a few years of personal research, he would write the first ever scientific book on fossils, Dissertation on a Solid Body Contained in Another Solid, two years later in 1669.

Steno would become the first person to suggest a theory for how fossils can find their way into rock, suggesting a theory for the formation of sedimentary rocks. Steno also laid the foundations for the later science of geology in this book, as he proposed some general principles for the arrangement of layers of strata found in mountains and hillsides.

Principle of Original Horizontality - The idea that gravity originally deposits strata horizontally, meaning any bends or folds in the strata are caused by later deformation of the rock.

Principle of Lateral Continuity - The concept that a continuous piece of strata may become divided due to a later erosion process that removes the portion of the strata where they were connected.

Law of Superposition - The idea that the lower or deeper a horizontal layer of strata is, the older it is, unless a later geologic process radically deforms the rocks.

Notable scientist Robert Hooke, most famous for his work with early microscopes, was the first to suggest, in a work published posthumously in 1705, that living creatures could be “petrified” into stone, and this explains the origin of all fossils. After Steno and Hooke, most scientists agreed that all fossils had an organic origin.

The identification of fossils as remains of living things was not without controversy, particularly when those fossils appeared to represent living forms that no longer exist and have thus gone extinct. This was difficult for some scientists and theologians of earlier days to accept, as it implied that the forms created by god were not immutable and unchangeable. John Ray, previously mentioned as a major figure in Natural Theology, felt that extinction was not possible for these reasons, something god would not allow. In 1695, he wrote

...since the first Creation there have been no species of Animals or Vegetables lost, no new ones produced. -- John Ray, 1695.

The science of geology quickly took off at the close of the Enlightenment. Coal mining, which had only begun in the 16th century, became a major industry by the end of the 18th century. This led to more scientific interest in study of strata which might contain coal, which in turn led to more scientists being exposed to fossils. In fact, early geologist William Smith was originally a coal mining engineer before his own personal interest in the fossils that were being recovered when digging for coal led him to study fossils as a hobby.

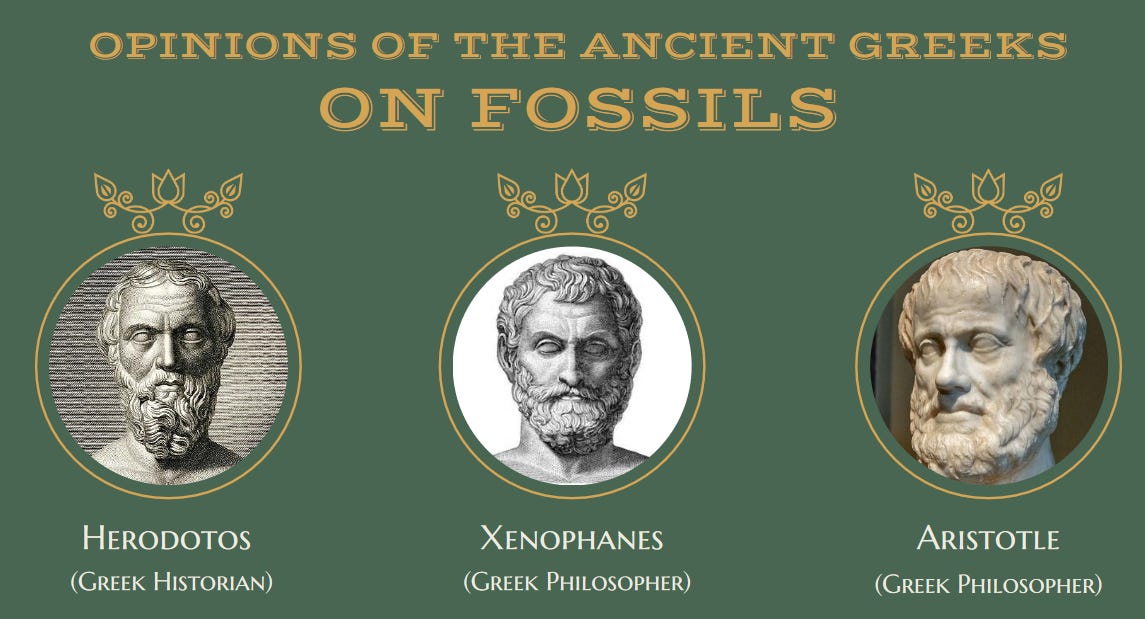

Between 1775 and 1796 three major theories emerged to explain the immense numbers of varying aquatic fossils found all over the world, as well as evidence of prior water action in deep fossilized strata.

German geologist Abraham Gottlob Werner proposed a theory he called “Neptunism” around 1775. He theorized that the earth had been flooded for vast ages, and the water gradually subsided to the current sea level, depositing all the strata, carving all the channels of water now seen to be dry, and leaving the various aquatic fossils found in high mountains as it gradually descended.

Scottish geologist James Hutton published Theory of the Earth in 1788. He suggested that slow geologic processes driven by volcanic activity continuously reform land into sea and back into land, resulting in a large number of strata permeated with aquatic animals. He called his theory “Plutonism,” but it and similar theories proposed later that explain geology as the result of slow continuous processes, would eventually all be considered forms of geologic Uniformitarianism.

French geologist Georges Cuvier argued in several of his books published from 1796-1812 that the divisions between strata were the result of “catastrophes” like floods or volcanic eruptions. A religious Christian, he theorized that different fossils were found in different layers because god remade the world each time he sent a new catastrophe. This theory would be dubbed “Catastrophism.”

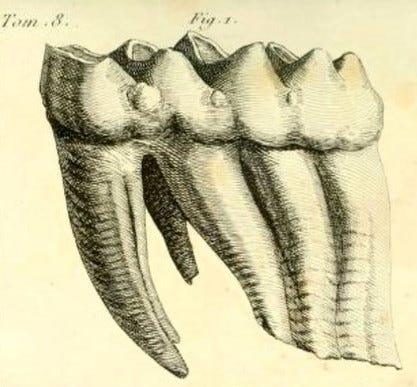

In 1796 Cuvier became the first scientist to demonstrate conclusively that extinction is real when he demonstrated that a fossil tooth from an elephant-like creature he obtained was not a match to a tooth from any living elephant species and must come from a similar extinct animal. He named the extinct species Mastodon, meaning “nipple-tooth,” due to the conical points on the top of the tooth which made it distinct. Cuvier was also the first geologist to extend Steno’s superposition principle to fossils, seeing all fossils in the same layer of strata as co-existing in the same time period, fossils in lower layers from earlier times. This fit nicely with his discovery of strata without mammals, living in a time period he called the “Age of Reptiles.”

Even though science was beginning to reveal that water had acted over much of the earth leaving fossils and indications of water action in places now dry, a fact that Neptunism in particular tried to explain, none of these scientists identified the Biblical flood as the sole explanation, despite the fact most were Bible-believing Christians who supported Natural Theology, because they all felt that the Biblical flood simply did not last long enough (a single 40 day event) to explain all the aquatic features worldwide.

All three of these geological ideas also required a vast age for the earth that could not be reconciled with Ussher’s chronology. Yet, the leading figures in geology were Christians troubled by the implications of their own findings on their religion. They sought to reconcile their own scientific findings with their Christianity.

In 1814, due to the growing consensus in geology that the earth must be more than 6,000 years old, Scottish Presbyterian minister Thomas Chalmers proposed that there could be any gap of time between each of the 6 days of the Biblical creation without contradicting the scriptural text. This idea would become known as Gap Creationism, and virtually all serious geologists (those who were not Deists) accepted the idea soon after it was proposed. However, it was not a perfect idea, as Genesis indicates god didn’t create the sun until the day after (s)he created plants.

When British geologists William Buckland (the first scientist to study dinosaur fossils) and Robert Jameson first learned of Cuvier’s Catastrophism theory, they believed it might offer an explanation compatible with Genesis. The Biblical flood would indeed qualify as a “catastrophe” under this theory, and it also offered a plausible scripturally-approved reason for extinctions, namely that god remakes his (or her) entire creation through periodic catastrophes. Extinction wasn’t so troubling if god did it intentionally. Plus, it proposed that extinct animals in each strata were special creations of god that were not related to earlier or later strata, and therefore did not require any theory of “transmutation” (evolution) to explain.

Although the Mosaic account of the creation of the world is an inspired writing, and consequently rests on evidence wholly independent of human observation and experience, still it is interesting, and in many respects important, to know that it coincides with the various phenomena observable in the mineral kingdom.

—Robert Jameson, foreword to an English translation of Cuvier’s work, 1815.

From 1833-1836 a series of books on scientific philosophy called the Bridgewater Treatises were commissioned by the will of a recently deceased rich aristocrat, Francis Egerton, 3rd Duke of Bridgewater, who wanted to assure that Natural Theology remained firmly dominant in science despite the controversial new findings of the age. Each of these books were written by different authors both scientific and religious, all advocating for Natural Theology, some also advocating for Gap Creationism.

Scientific interest in Catastrophism waned after Charles Lyell wrote Principles of Geology in 1833. Principles made compelling and influential arguments in favor of the geology we see on earth being the result of long, slow “uniform” processes rather than periodic catastrophes. Cuvier, a vigorous debater and the biggest intellectual defender of Catastrophism, died of cholera the year before it was published, and was not able to counter Lyell. Uniformitarianism would dominate geology by the 1840’s.

Lyell studied the strata of Mt. Etna and surmised that there was too much similarity between organisms in adjacent strata to have been the result of different creations as required by Catastrophism. Lyell pointed to the ruins of a Roman marketplace in southern Italy, which was known to have somehow been submerged at some point in the past due to the fact the ruins contain holes made by mollusks. This meant the columns had been submerged and then later re-emerged without there having been enough “catastrophic force” to make them topple in either case. It was later understood that shifting magma caused the ground to rise and fall.

The shift away from Catastrophism and towards Uniformitarianism in the 1830’s and 1840’s resulting from the impact of Principles of Geology rekindled interest in evolutionary ideas, although Lyell himself vigorously opposed the concept of evolution at the time he wrote Principles and even added content to the second edition expressly condemning evolution and any notion that his ideas necessarily pointed in the direction of evolution.

The idea that species may have evolved or “transmuted” over time was first proposed in antiquity by Alexander of Miletus sometime after 600 B.C.E. However, the highly influential Platonic Greeks argued later that life forms do not change and this became accepted Catholic dogma. Due to this and the Genesis creation account, both Catholic and Protestant leaders agreed that god created life only in unchanging forms.

Benoît de Maillet, a French diplomat, penned what was possibly the first philosophical speculation since antiquity that both that the earth may be extremely old and that life, including humans, have evolved from simpler forms, in his work Telliamed (1722-1732). He gained this impression from seeing many different landscapes around the world in his travels.

The first person in scientific circles to propose any concept of evolution was the Comte de Buffon, who proposed in his highly influential work on taxonomy, Histoire Naturelle (1749), that similar organisms evolved from a “base” ancestor of each type, which may in turn have come about via spontaneous generation.

Erasmus Darwin, the grandfather of the more famous Darwin, wrote the first work to suggest that all life on earth, not just similar types, might have evolved from a single common ancestor, in his epic taxonomic work Zoonomia (1794-1796).

In 1809 Jean-Baptiste Lamarck wrote the first systematic theory of evolution in print, Philosophie Zoologique. This theory proposed that organisms can influence their forms by taking on different habits, which would cause biological changes in descendants. Famously, he suggested that giraffes directed the evolution of their own necks by willing them to grow longer out of necessity, over a period of many generations.

A colleague of Lamarck, Geoffrey St Hilaire, noticed that many seemingly different animal species actually share the same “morphologies” (for example, the same number of bones in each limb, but the bones may be in different shapes based on the particular animal).

He proposed a theory of evolution in which the “base plan” doesn’t change, but infinite varieties of that plan are possible, depending on the habitat an animal finds itself in. This idea is similar to the one proposed earlier by Buffon but is more specific about what is meant by a “similar type” which can evolve.

While all the major geologists discussed earlier accepted a very old earth contrary to the Biblical creation account, initially only the Deist James Hutton was willing to accept that evolution might have occurred. The others, and indeed the entire establishment of science at the time, deeply influenced by Natural Theology, saw ideas of evolution as fundamentally incompatible with scripture because evolution implies god did not specially design any lifeform except possibly the first one, or first one of a “type”, denying more aspects of the Biblical creation than just the timing.

A process of evolution also makes it implausible that god created humans in his own image directly as indicated in Genesis 1:27, as that would imply god himself followed the same evolutionary processes that led to our appearance, or somehow fitted our evolutionary path to result in our resembling him.

Meanwhile, another scientific question with religious significance began to be considered at around the same time as the new ideas in geology and paleontology. This was the question of how the earth and solar system came to exist. Today we have ample scientific evidence that the solar system (and indeed all star systems) originated as cosmic gas and dust which condensed under its own gravity, an idea which is called the Nebular Hypothesis.

Issac Newton established the principle that the force of gravity acts everywhere and upon all things in space and on earth in his Principia Mathematica (1687), and then about 75 years later, influential German philosopher Immanuel Kant was first to propose the solar system condensed from space dust under its own gravity in his Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens (1755). Pierre-Simon Laplace, apparently unaware of Kant’s work, proposed the same idea along with mathematical formulae for how it could work in his Exposition of the System of the Earth (1796).

The nebular hypothesis was unsettling from the perspective of Natural Theology because it suggested that the processes which formed the solar system were not unique and probably also formed other star systems, and that therefore the universe must be full of planets, which is something we have only recently begun to directly prove with modern space telescopes. A universe full of planets is probably also full of other forms of life, and probably also full of intelligent life, or at least, both of the major thinkers who considered the subject prior to the year 1800 (Giordano Bruno and Bernard Fontanelle) came to that conclusion.

Any life on another planet would require another divine creation, and the Biblical creation implies the existence of only the “heavens” and the earth, without mention that god created any kind of life in the “heavens”. Worse, the idea of intelligent life on other planets calls into question the special relationship between man and god in the creation account. It is also worth mentioning that the Platonic Greek thinkers that had so much influence on Christian thought argued that the earth is the only habitable world in the universe, believing everything outside of the earth, including the sun and other planets in this solar system, were all made out of “aether.”

PART 3 soon—probably next week.

Note: Anyone may copy and publish what I or my guests write, provided proper credit is given, that it’s not done for commercial purposes, that I am notified of the copying (you can just leave a comment saying where the copy is being published), and provided that what we write is not quoted out of context or distorted.

Thanks again for reading Letters … . Subscribe for free (always) to receive new posts and support my work.

Great summary of this crucial history! I have to add one famous anecdote: The story goes that Napoleon asked Laplace to explain the nebular hypothesis to him. When he had finished, Napoleon inquired, "But where does God fit into this account?" Laplace replied, "Sire, I have no need of that hypothesis."

Paul, well done. This is a clear, concise review of how the effort to understand fossils and geology led to the realization that earth and species have a complex history—and the impact on natural theology.