Numbers!

Monday--15 December 2025

The Numbers of Our Lives—Part One

Our lives are saturated with numbers, some trivial, some important, and many not well understood. I fancy myself as being better able to sort some of this out than some can, but I certainly invite any readers to correct or question me.

Compound Interest

Compound interest is too much of a topic to adequately address in a short section, but one example may suffice to make clear that everyone needs to have some grasp of these numbers. This has great potential practical importance—so we should all pay attention in a consumer education class if we get the chance.

If you pay $1000 a month to a lender (or invest it; or pay it in a mortgage) for 30 years, you’ll have put $360,000 into the effort. But what has the total value of this been if you were paying—or earning—a modest 6 percent annual interest on it? The answer is about one million dollars—between two and three times as much as you put in. (The exact answer varies based on compounding each month or each quarter, when interest is applied, etc.) And a higher interest rate makes for a dramatically higher total: 10% per year—close to the rate the US stock market returns annually on average—would yield a total of almost $2 million—between 5 and 6 times as much as you put in.

So look for ways to earn compound interest—and realize that paying it will make you more likely to be in the wrong half of “The rich get richer and the poor get poorer,” as Percy Bysshe Shelley probably first said.

Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822)

Comics

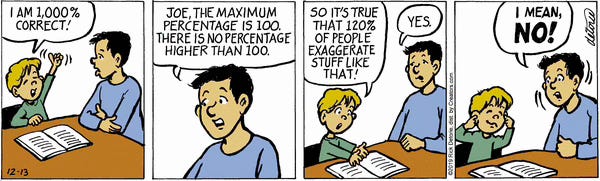

Comic strips in your daily newspaper (you remember those, don’t you?) often use numbers in hopes of getting a chuckle. For example, from Rick Detorie, who draws One Big Happy—

and

Now of course you can have more than 100%—”the market has been up 120% over the last few weeks” may not be a true statement, but it is at least a possibility.

But your coach was wrong when he demanded that the players all “give 110%.”

Mean versus Median Regarding Money

The three most common measures of central tendency, intended to reduce a bunch of data to something easier to grasp and more manageable, are mean, median, and mode. If I gave you a list of all eight million names and their net worth for everyone in Georgia, you might find it interesting but not clear as to meaning.

If I advise you that the “average” net worth of Georgia families is $57,000, that would be an example of reducing lots of data to a more meaningful measure of central tendency. (I have no real idea of the correct number, by the way.) But “average” is an imprecise term. Most of the time it means the same as arithmetic mean—in this case, the total net worth of all Georgia households divided by the number of households.

Mode—usually not a very good measure of central tendency in matters related to money. If I told you the mode in Georgia for wages is $7.25 an hour, that would mean there are more people making the minimum wage than any other specific pay.

And the “mean” would very likely be quite misleading. In this state as in the US in general there is great wealth inequality. And thus the top one percent richest Georgians would distort the mean considerably.

Imagine there are eleven households in the block or building where you live. If one household has a net worth of $25 million, one a net worth of $1 million, two $75,000 each, one $50,000, and the other five $5,000 each, the mean would be $2,622,500. That would be mathematically correct but far from meaningful as a representative account of wealth for those eleven households.

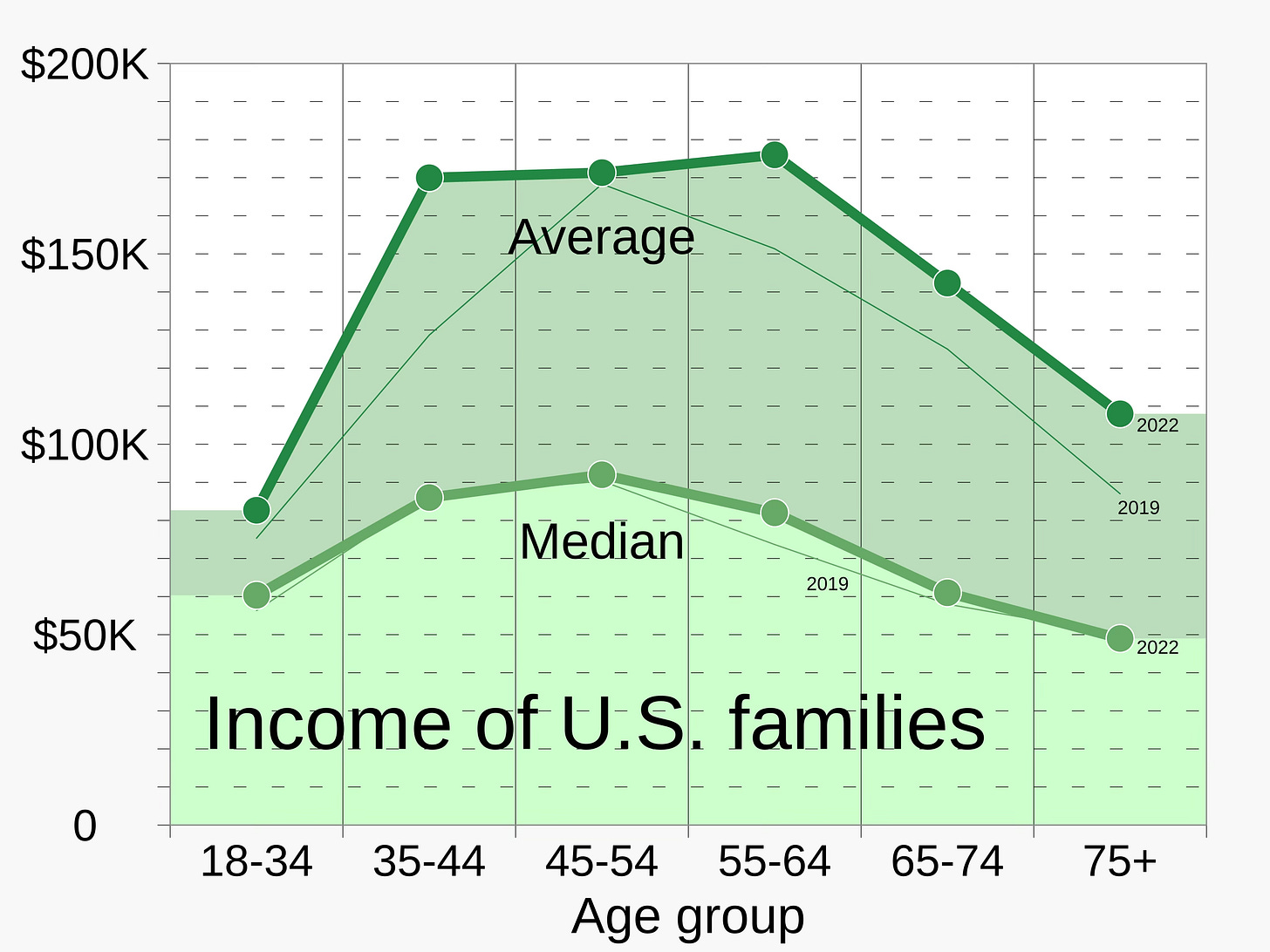

The mode would be $5,000—also correct but not very telling. The median—the number that has the same number of households above it as below it—would be $50,000. That wouldn’t tell you about that really high one or the lowest ones, but it’d be a much more reasonable population measure. When it comes to money—income or wealth—median is usually better. In the chart below, “average” is the mean—and it’s a great distortion no matter what age group you’re looking at. In every age group, the richest families at the top pull the mean way up. For most of the age groups “average” income is two or three times as high as the median.

For much more detail, see—

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Household_income_in_the_United_States#/media/File:2022_Average_and_median_family_income,_by_age_-_US.svg

Penalty for Violating the Sabbath—

Those of us who lack any religious belief are quite unlikely to worry about the Sabbath—Sunday (or maybe Saturday or for Muslims, Friday). We—most of us anyway—are content to let religious people worry about such matters, other than maybe not being able to buy beer or wine when we like.

But for those who take Scripture literally and really seriously, breaking the Sabbath is a major deal:

Old Testament, Numbers 15: 32-36

According to the Old Testament book of Numbers, those who violate the Sabbath must be stoned to death by their neighbors:

32 Now while the children of Israel were in the wilderness, they found a man gathering sticks on the Sabbath day. 33 And those who found him gathering sticks brought him to Moses and Aaron, and to all the congregation. 34 They put him under guard, because it had not been explained what should be done to him.

35 Then the Lord said to Moses, “The man must surely be put to death; all the congregation shall stone him with stones outside the camp.” 36 So, as the Lord commanded Moses, all the congregation brought him outside the camp and stoned him with stones, and he died.

My excuse for including this here is of course the name of the Bible book. Happily, none of my neighbors seem to read the Bible this way (if at all). Me and all those professional baseball players who swing their sticks around on the Sabbath are happy that’s rare.

Another Magic Number—”666”—The Number of the Beast

And from the the New Testament Bible book that Thomas Jefferson called the ravings of a madman, the Book of Revelations, Chapter 13—

18 Here is wisdom. Let him that hath understanding count the number of the beast: for it is the number of a man; and his number is Six hundred threescore and six.

Threescore is of course, three times twenty, or sixty. Again, those without religion see the number “666” as nothing more than quaint or weird. And I suspect the great majority of Christian believers also happily ignore this one.

But I did witness a store cashier in the Buffalo, NY, area who quite seriously urged a customer to buy one more thing, because the change she was due was $6.66. The customer laughed it off, but the cashier looked genuinely upset.

S&P 500—Why the Rich Are Different

Two guys (make ‘em women if you’d rather)—one (Richard—Rich for short) has 28 million dollars, 25 million of it invested in the S&P 500 stocks. The other (Notso—Not for short) has a net worth of $37,000, of which $20,000 is invested in the S&P 500 stocks.

On a given day (or week if you’d rather) the S&P 500 Index goes up (or down) a half a percent. In the great scheme of things, that’s merely a fluctuation—and should be ignored, not fretted over.

For Notso, that fluctuation amounts to $100. So old Not can withdraw his winnings and probably have enough, after paying his broker fees, for a tank of gas or a decent meal out.

At the same time Rich “earned” $125,000, so he can buy a pretty nice new car or enough diesel for his yacht.

There’s just no way that Rich and Not can have the same attitudes about life and money, according to the numbers. And Shelley’s aphorism applies here, too.

Much more—

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/12/14/opinion/billionaires-politics-money.html

Next week (or later, if events inspire some other Letter, as now seems likely), Part Two on numbers, including—

Seconds to Days or Years—What’s a Billion Anyway?

CEO Pay as Multiple of Line Worker’s Pay

Elite Rich as Proportion of Everyone—Why Does it Matter?

National Debt

Cost of a Program or Benefit Per Person or Per Household

And, Most Important, CONCLUSION: Perspective

Related Letter of yore (20 March 2023) on inferential logic—

Note: Anyone may copy and publish what I or my guests write, provided proper credit is given, that it’s not done for commercial purposes, that I am notified of the copying (you can just leave a comment saying where the copy is being published), and provided that what we write is not quoted out of context or distorted.

Thanks again for reading Letters … . Subscribe for free (always) to receive new posts and support my work.

Donald Trump says that he reduced the cost of something by 1500%. That means that if it cost $10, it is now free and they pay you $140 to take it.

Great exposition on mean, median, mode. A modest proposal to lessen skewing of income and wealth data in the US; provide amended charts showing income & wealth mean - median - mode when exclude the bottom 2 million and top 2 million households. 🕊️