About the Friday Freethought Perennials in general: This subset of my blog is to answer questions, nearly always already answered by me and by many others but posed again and again—over many years and in many places—on freethought, atheism, secular humanism, secularism/church-state/”This is a Christian Nation,” and similar topics. These answers are mostly not intended to be original analyses, breaths of fresh air, so much as just putting a whole series of things on the record (I’d say “forever,” except I know better). One source for many of these answers is the 2012 Prometheus Books book by me and my son (Michael E. Buckner), In Freedom We Trust: An Atheist Guide to Religious Liberty—and that is where footnotes and careful citations of sources can be found. It’s available in many libraries and pretty readily in the used book after-market. I’ll cite writings of others that answer these things in more depth if I’m aware of them when I post these.

If We Are Not For Christianity (or Other Matters), Are We Therefore Against Christianity (or These Other Things)?

I’ve written before about neutrality—see links below—and I don’t claim that this Letter is wholly new—but it is broader in scope than those earlier efforts. Those focused on state neutrality regarding religion, and this time I do that, too, but as part of a discussion of neutrality in other matters, too.

Neutrality—A Desirable End?

Is neutrality desirable for its own sake, in all matters or in some? If only some, why those?

Neutrality is not inherently and permanently worthwhile in any case, but it is necessary in some cases and objectionable in others.

There are times when neutrality is not positive at all, but a distinct negative—even sometimes a morally repugnant, cowardly stance. And it is at other times just the only reasonable stance. We don’t have any real basis for deciding whether life exists on planets millions of light years away, so the reasonable person will avoid coming to any conclusions until we have at least some grounds for deciding. Saying, “I don’t know” in such a case is a form of neutrality that is quite wise.

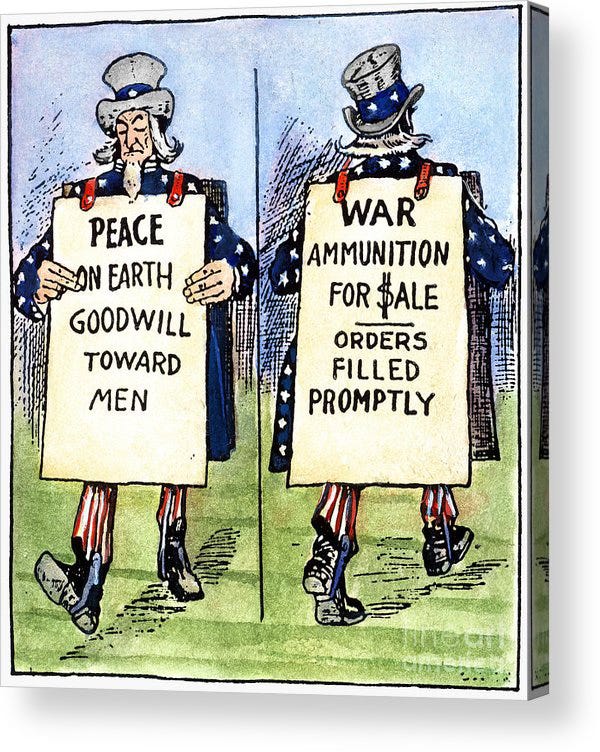

And false neutrality—hypocritically posing as neutral when you’re anything but—is another form of morally unacceptable neutrality.

Religion

What if there is evidence or a set of facts that some think is conclusive, while others don’t think the evidence is telling at all? What if some have prayed to Allah and studied the Qu’ran and are quite sure of His desires and commands and that mere humans must submit? What grounds can anyone possibly have for rejecting such clear and important knowledge?

War

I’m not close to neutral regarding Hamas’s vicious attacks on Israeli civilians on 7 October 2023 or on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (starting in Crimea in 2014 and escalating dramatically almost exactly two years ago (24 February 2022), because I see a clearcut, unjustifiable aggressor in both cases. If someone could show me clear counter facts, I would change my mind.

Church & State

And that, I submit, is the crucial difference between many other matters and religion.

It really isn’t a matter of accepting versus rejecting religious truth or God or even one’s perceived lack of evidence that God does exist. The Muslim I mentioned above and my neighbor who has identified me as her “mission field” and some of my atheist friends are all sure they’re right, sure that religious truth is right in front of them. But unlike a clear commitment to one side or another in a war, the accurate interpretation of evidence to get to truth is not open, even in principle, to the believer or nonbeliever in ways beyond doubt.

That doesn’t mean there’s no way I could be wrong about Hamas or Putin or that there’s no way a Christian could be wrong in the same sense. It means that there are facts, even if not all necessarily known by me, that if known would confirm (or refute) my conclusions—but no parallel facts regarding any important religious beliefs.

Is real neutrality possible? Probably never quite. Is it desirable? It depends. And can we hold complex conclusions without being attacked for being “on the wrong side”? For all of us—yes, please.

If facts are not available, neutrality in some sense is necessary. If facts are available and the matter is important, it’s important to learn the facts and not be neutral, or especially not rigidly immune to the facts at least.

Examples to contemplate—

https://wapo.st/42FMfeI

https://whyevolutionistrue.com/2024/02/15/the-myth-of-the-two-state-solution/

Earlier related Letters—

Neutrality and Blasphemy (Part 2 for Each)

Before I post today’s Letter, let me warn you—and no, I don’t know how you should prepare for this (just do the best you can)—I’m taking next week off. No posts at all on the week of 16-20 October. I’ll be lavishing attention on a loved one in honor of her birthday, not attending to you lot. Deal with it.

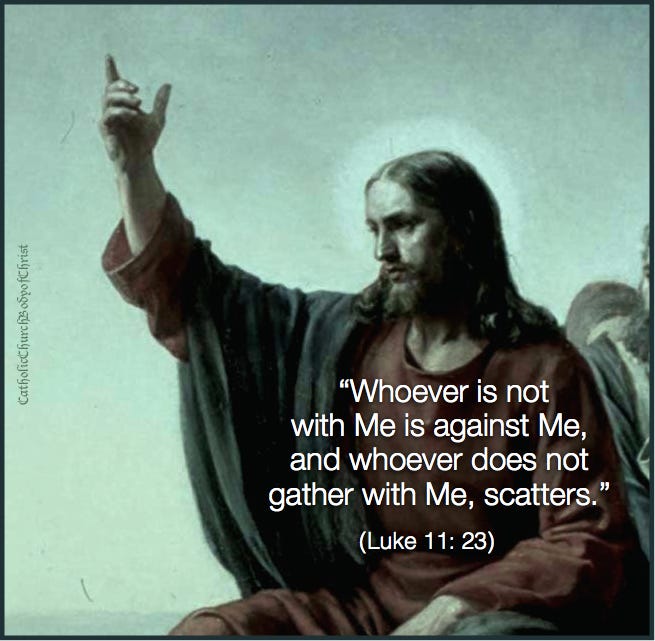

"He That is Not With Me is Against Me"?

About the Friday Freethought Perennials in general: This subset of my blog is to answer questions, nearly always already answered by me and by many others but posed again and again—over many years and in many places—on freethought, atheism, secular humanism, secularism/church-state/”This is a Christian Nation,” and similar topics. These answers are most…

Note: Anyone may copy and publish what I or my guests write, provided proper credit is given, that it’s not done for commercial purposes, that I am notified of the copying (you can just leave a comment saying where the copy is being published), and provided that what we write is not quoted out of context or distorted.

Thanks for reading Letters to a Free Country! Subscribe for free—always/guaranteed—to receive new posts and support my work.

A few decades ago, now, Rorty penned an essay, "Is Religion a Conversation-Stopper?" I think his instinct was correct, but his execution uncharacteristically abominable. Instead of answering the question, he complained of the oppression of the agnostics in American life, and there's no way to do that, especially with his profile, and hot come off whiny.

The point -- and it's one that Compositionists would do well to learn -- is that conversation in the public square is not a matter of marshaling one's evidence. and especially not of announcing ad nauseam one's identity, but if finding a language common to the collective, which in the US case happens to be extremely diverse. Here, I think Rorty's intellectual father William James is useful for teaching how to avoid distinctions that do not mane any significant difference.