Keith Parsons: Science--Good Stuff?

Wednesday--22 October 2025

Another great guest essay by Dr Parsons—

WHAT IS SO GREAT ABOUT SCIENCE?

Here is something that has definitely changed for the worse in the sixty plus years since I was a child. At that time, science was venerated. No activity was more important than scientific research. No vocation was higher than to be a scientist. Science was so honored that people were happy to accept Werner von Braun (1912-1977) as the smiling, avuncular public face of science. Nearly forgotten was the fact that von Braun had been a Nazi and was the deviser of the V-2 rockets that rained destruction on London.

Tom Lehrer (1928-2025)

Satirical songster Tom Lehrer (recently deceased) remembered:

All the widows and orphans in old London town

Owe their large pensions to Werner von Braun.

“Once the rockets go up, who knows where they come down?

That’s not my department,” says Werner von Braun.

Von Braun sued, but the suit was tossed. Unlike Nazi Germany, America has free speech.

These days, popular ideologies and powerful politicians hate science and obstruct, obscure, and censor it. Scientists are vilified, deprived of funding, and, if employed by the government, fired en masse. A notorious crackpot is head of the Department of Health and Human Services, making a total fool the highest-ranking official charged with the protection of public health. The internet and social media are full of quack cures and bogus claims, such as that horse dewormer is an effective treatment of COVID, and the lie that will not die—that vaccines cause autism. A hard core of climate-change deniers is impervious to all evidence, even as this year’s thousand-year flood washes away their homes. Unfortunately, some of those invincible deniers now run our government, so that climate change, the greatest existential crisis facing humanity, is ignored.

It should be needless to say that it is very dangerous when those in charge despise science. Science phobia is also a personal issue with me. I love science and always have. Had I been a bit more mathematically adroit, I would have entered physics rather than philosophy. Now I content myself by being a science booster and defender. What, then, to me is so great about science? Here are the three greatest things I learned in school: The extent of the cosmos, the depth of time, and atoms, the world within the world.

Extent of the Cosmos

How big is the universe? You can give numbers, but the numbers do not really give us a feeling of the true immensity. They cannot. We cannot imagine it. Consider a map of our galaxy, the Milky Way. Imagine that the map is as large as North America, extending from Baffin Island in the north to the Darien Gap in the south. On this scale, Earth would still be molecule-sized. Astronomical distances are given in light years. Light, electromagnetic radiation, is incredibly fast—186,282 miles per second or 299,792,458 meters per second in a vacuum. A radio signal sent to the Moon arrives in less than two seconds. Yet, at that incredible speed it would take 100,000 years for a beam of light to transverse the diameter of the Milky Way. And ours is only one of hundreds of billions of galaxies. This year is thirty years since the Hubble Space Telescope took its most iconic image, the Deep Field. The scope was aimed at an “empty” patch of sky. When the image was obtained, the “empty patch” was full of distant galaxies. Worlds without end.

I once heard of someone who said that size did not impress him. After all, a fat man is not necessarily more impressive than a thin one. True, but if the Grand Canyon were only twenty feet deep, it would not be grand. Like Teddy Roosevelt, I admire big forests and big mountains. Big universes too.

The Depth of Time

The extent of space leads directly to an appreciation of the depth of time. If you go to a dark sky site far away from city lights on an autumn night, then, if you have good eyesight, you might be able to detect the most distant object visible to the naked eye—the Andromeda Galaxy. Andromeda is a mighty spiral galaxy, bigger even than our own, and a part of our “local group” of galaxies (Astronomers have an idiosyncratic understanding of “local.”). Andromeda is 2.537 million light years from us. So the photons hitting your eye began their journey 2,537,000 years ago. At that time, Homo habilis, the first member of our genus Homo, may have just put in an appearance.

Just as the universe is incomprehensibly big, so our Earth is incomprehensibly old. The last T. rex died 66 million years ago. How long ago was that? Imagine a distance scale where one inch represents a hundred years, about the maximum extent of a human life. On that scale, going back twelve inches, one foot, would put us in the Dark Ages, when the Vikings were ravaging Europe. Two feet, twenty-four inches, would put us in the age of Plato and Aristotle in classical Greece. Three feet, thirty-six inches, would put us well back into the Bronze Age when The Epic of Gilgamesh was a bestseller. On this scale where one inch equals a hundred years, we would have to go over ten miles to get back to the end of the time of the dinosaurs. And by the time of the beginning of the dinosaur age, Earth was 95% of the age it is now. Mark Twain (1835-1910) noted that if the history of Earth were represented by the Eiffel Tower, human history would be the skim of paint on the very top.

For centuries, under the tutelage of the Book of Genesis, Christians thought that the Earth was only about 6,000 years old (Hindus had already recognized an ancient universe.). Some even claimed to nail down the calendar date and the time of day of creation! (Eden Standard Time, I guess.) You can see why, at the end of the eighteenth century, when geologists first began to realize Earth’s true antiquity, that one of them said that he had a sensation of giddiness as if standing at the precipice and peering into the abyss of time. He made this pronouncement after observing Siccar Point on the coast of Scotland. Here ancient (Silurian) sedimentary strata, originally deposited horizontally, had been tilted almost vertically by geological forces and a considerable depth of younger (Devonian) strata layered on top. This formation speaks of ages before ages in the oceanic depths of time.

Most wonderfully, those depths of time were full of wondrous creatures, like something from a storybook (or nightmare) but real. Dunkleosteus, the thirty-foot, armor-plated terror of the Devonian seas, would have made the great white shark look like a tuna. The Jurassic was the age of true giants with sauropods as long as two city buses and weighing as much as a herd of elephants. Most famously, there was T. rex with a head the size of a bathtub and jaws lined with serrated steak knives the size of bananas. Living in the Los Angeles area 10,000 years ago, and surely known to and dreaded by the Paleoindians, was Smilodon, a sabertoothed barrel of muscle who could take down the biggest bison.

Atoms, the World within the World

Ever since van Leeuwenhoek in the seventeenth century first observed microorganisms by microscope, we have known that there is a whole world below the realm of visibility—a world within the world just as variegated and rich as our mid-sized world of shoes, ships, sealing wax, cabbages, and kings. We live in an ocean of bacteria, and for bacteria, we are the ocean that they live in. We carry approximately as many bacterial cells in our bodies as we do our own cells. Most of the bacteria are harmless or beneficial. The ones that get attention are the pathogens, and some are truly nasty. Yersinia pestis killed a third of humanity in the fourteenth century. I just got my DPT (diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus) vaccine. You really want to keep up with this one. The tetanus bacterium secretes a neurotoxin that causes muscle spasms so intense that they can break bones.

Viruses are fascinating and even scarier. They are not really organisms but molecular machines that function by taking over your cells and turning your genetic machinery into a factory for producing more virus. Darwin sometimes mischievously played the role of “devil’s chaplain,” citing the horrors of nature. The hemorrhagic fevers would probably provide the best examples. Richard Preston’s book The Hot Zone (1999) is about Ebola. Most viruses attack a particular type of tissue, such as the pulmonary system. Ebola attacks everything, turning every cell into an Ebola factory. In short, said Preston, Ebola is turning you into it. When I read this line, the few remaining hairs on my head tried very hard to stand up.

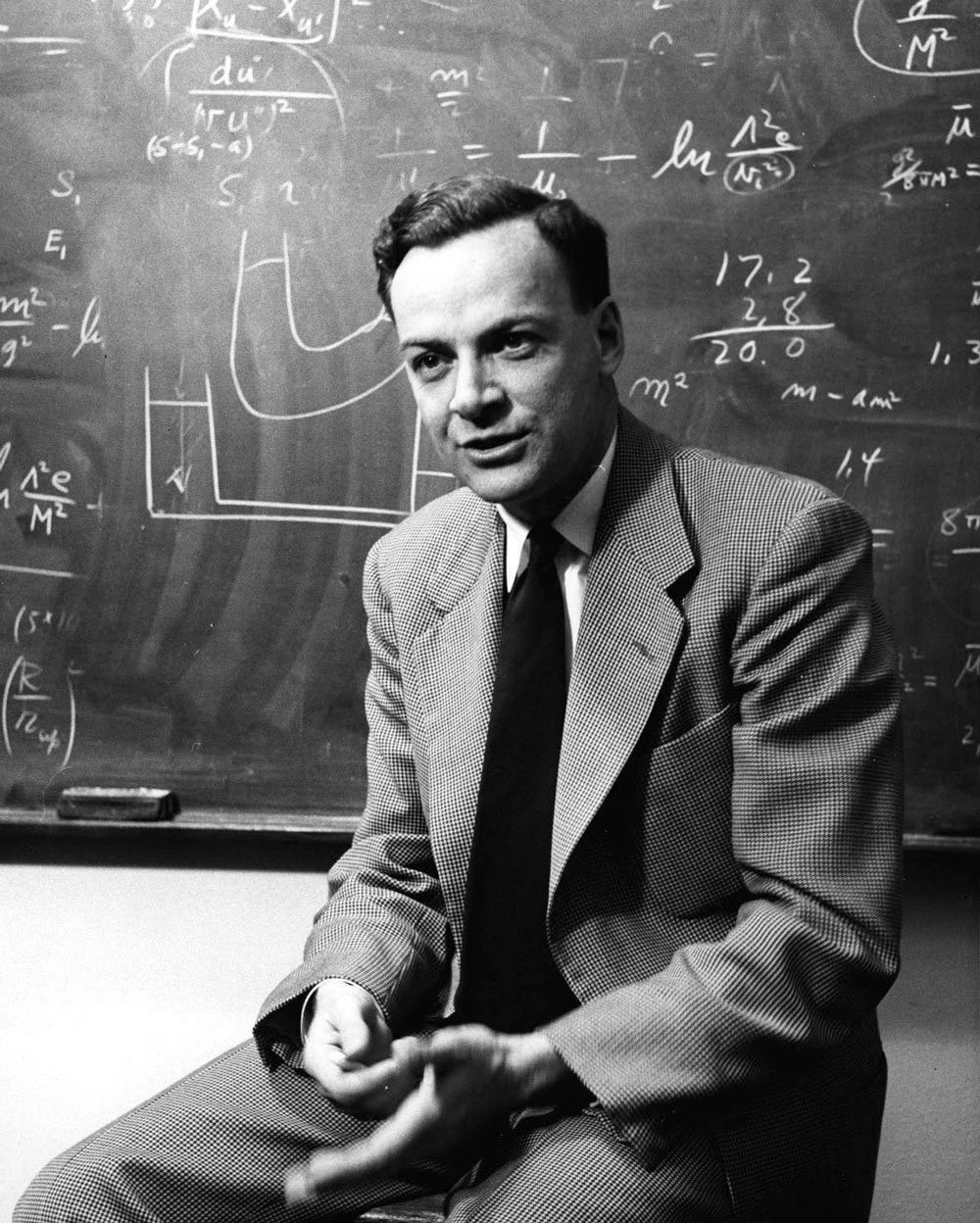

Richard Feynman (1918-1988)

Yet there is a world even smaller than the world of microorganisms. Richard Feynman, often considered second in brilliance only to Einstein among the physicists of the twentieth century, said that if all scientific knowledge were destroyed except for one idea, that idea should be that all things are made of minute particles called atoms. The evidence that things are composed of tiny invisible particles has been known since ancient times. In the Vatican, there is a bronze statue of St. Peter that dates back at least to the middle ages. I have seen it. For centuries, pilgrims have piously touched or kissed St. Peter’s foot. A single touch by a single pilgrim of course has no visible effect on the bronze, but the devotion of millions of pilgrims over many centuries has worn down the bronze, atom by atom.

Yet at the beginning of the twentieth century, there were still physicists and chemists who doubted the existence of atoms. Then, in 1905, a twenty-six year old patent clerk in Bern, Switzerland published four papers in the journal Annalen der Physik, any one of which could have won him a Nobel Prize—and one did. One of the papers of Einstein’s annus mirabilis showed mathematically that the phenomenon of Brownian motion—the random movement of tiny particles suspended in liquid—could only be explained in terms of the impacts of innumerable invisible particles—molecules. Soon, even the hardboiled atomic skeptics were won over.

Every item of our experience is composed from some of just 92 naturally occurring elements and their 339 known naturally occurring isotopes (Different isotopes of the same element will have the same chemical properties but will differ in weight because their nuclei contain different numbers of neutrons.). Of these 339, 251 are believed to be stable, while the rest exhibit the fascinating property of radioactivity, the processes whereby their nuclei spontaneously decay, releasing energetic particles and transforming themselves into other elements. Marie and Pierre Curie used to entertain dinner guests by turning down the lights and passing around containers of glow-in-the-dark radioactive substances. Holy shit.

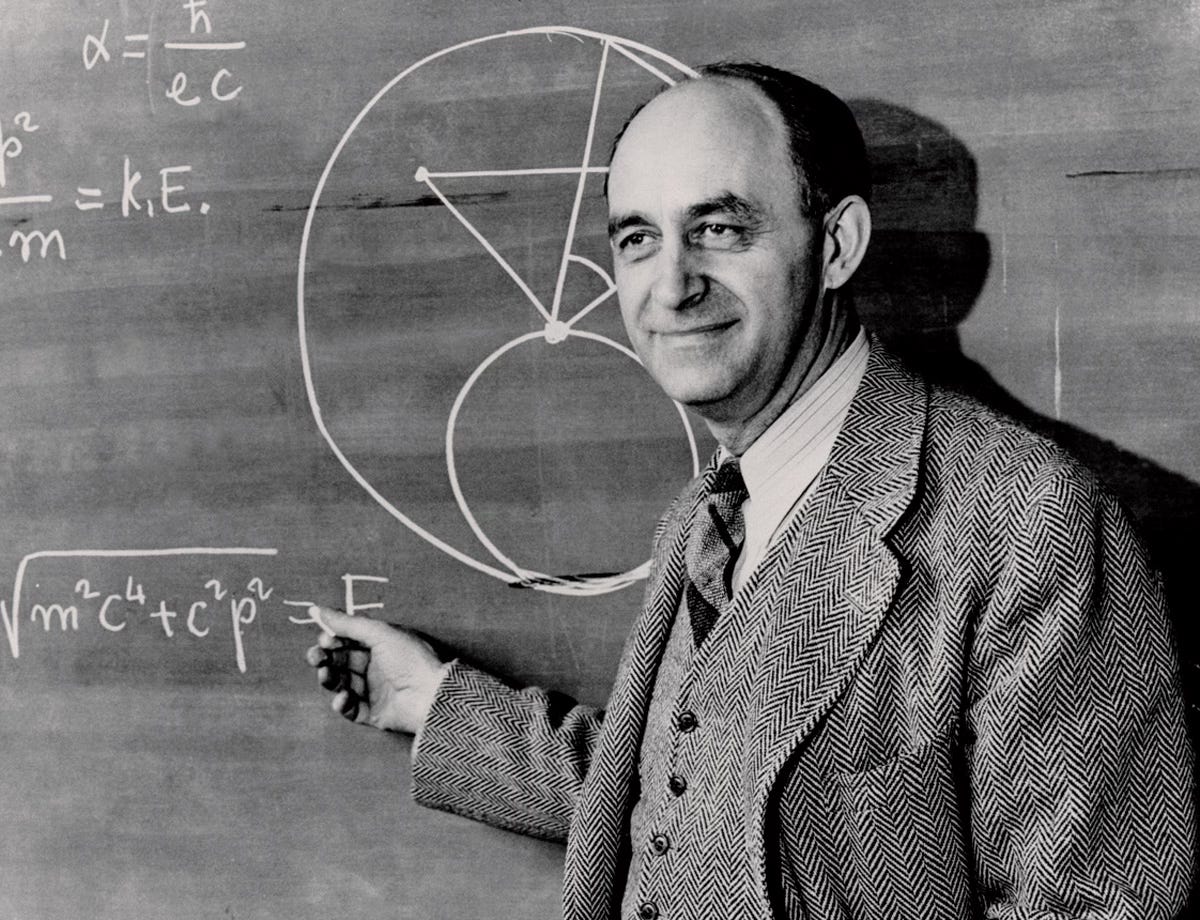

Enrico Fermi (1901-1954)

We have been in the “atomic age,” when, for good or ill, energy is obtained from nuclear forces, for about eighty years. The first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction was achieved at the University of Chicago in 1942 by Enrico Fermi and his team. Just eighty years ago last July, on the 16th, the Trinity Test proved that the plutonium implosion bomb developed by the Manhattan Project worked. Spectacularly. Brighter than a thousand suns. On the 6th and 9th of the next month, atomic bombs were dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, instantly killing tens of thousands, and ultimately 200,000. The effects of nuclear weapons on human beings are exceedingly horrible. The image that really got to me was the picture of a woman whose flesh had been burned with the pattern of the kimono she had been wearing when the bomb flashed.

The story of the development of nuclear weapons is fascinating because objects of unparalleled destructive power were products of the most beautiful and brilliant physics. The beauty and the horror are captured best by Richard Rhodes in The Making of the Atomic Bomb (1986) and Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb (1995). Even when dealing with horrible things like the Ebola virus or thermonuclear weapons, the science that studies them is fascinating and wonderful.

The universe was not made for us. We were not meant to be here. We are apes granted intellect by cosmic accident, and with us the universe has become self-aware. Our ignorance infinitely exceeds our knowledge, but, as Einstein observed, the little that we know is our most precious possession, and those who would deprive us of that possession are our vilest enemies.

Note: Anyone may copy and publish what I or my guests write, provided proper credit is given, that it’s not done for commercial purposes, that I am notified of the copying (you can just leave a comment saying where the copy is being published), and provided that what we write is not quoted out of context or distorted.

Thanks again for reading Letters … . Subscribe for free (always) to receive new posts and support my work.

I recall the date of creation being on a panel of quotations (some scientific, others not really) about earth's history, and the good prelate worked it out to a Saturday in October.

I accept that. God in His wisdom clearly recognized that his Saturday was nothing without college football.