Keith Parsons: Reasons for Unbelief, Part I

Guest essay, Monday, 14 April 2025

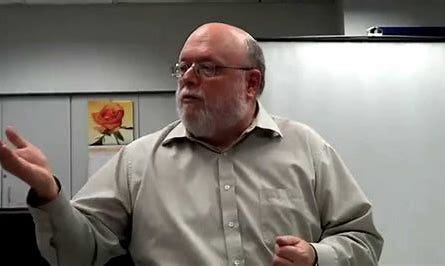

Turning over this whole week to my friend and philosopher I respect hugely, Keith Parsons.

DON'T BELIEVE

Keith M. Parsons!

1989 book (Parsons has been analyzing this for decades)

God? Smaller than Keith, am I right?

Part I

Conservative pundit Ross Douthat has recently published Believe: Why Everyone Should be Religious. However, in this time when aggressive Christian nationalists seek to impose a theocracy, it is important for secular people to remind themselves why they don't believe, and why unbelief is an eminently reasonable and salutary position. I have been an atheist for nearly fifty years. During that time some of my beliefs have modified. As a militant young convert to atheism, I wanted nothing more than to drive the last nails into the coffin of Christianity. My view of Christianity is now more nuanced, and I am happy to count among my closest friends two retired ministers and another lifelong devout Lutheran. I do not see these friends as in any way unreasonable or superstitious people. Their examples and many others show me that religious beliefs may be held thoughtfully and with integrity.

Yet my core atheism has not changed. I see no reason to believe in God, gods, or indeed any supernatural agents, like ghosts, demons, or souls. I do not say that physical entities are the only things that exist. Numbers, sets, possibilities, and meanings surely exist in some sense. What I deny is the existence of non-physical beings who have the power to act as causal agents, who can bring about effects in the world, as, for instance, by performing miracles, answering prayers, making revelations—or even, like Marley's Ghost, rattling chains and uttering ghastly moans. Concomitantly, I reject all purported religious revelations and creeds, seeing them all as equally baseless. Here, then, I would like to offer three reasons for unbelief. I explored a fourth reason in an earlier essay (Letter!) on "the problems of evil" and will not repeat those arguments here ("Problems of Evil," 8/21/24).

1. No purported revelation is believable

If God exists, then surely he has, at some time or another, revealed to humanity his existence and will in a manner that is clear, definitive, and authoritative. Immediately, though, we run into the problem noted by Mark Twain when he trenchantly observed (paraphrased) that humanity has discovered the One True Religion. Lots of them. In other words, religious pluralism is an undeniable and unavoidable fact. Several different and conflicting sets of scriptures have claimed status as divine revelations, the Word of God. Prominent examples are the Jewish and Christian scriptures (Old and New Testaments), the Book of Mormon, and The Qur'an. Each of these purported revelations has deep and serious problems. Here I will focus on the Jewish and Christian scriptures since they are the ones most familiar to me and, I presume, most readers.

That the Old and New Testament literature is not to be taken at face value has been known for hundreds of years. Even the church "father" Origen of Alexandria (third century CE) recognized that much of scripture, if taken literally, is trivial or absurd. He therefore recommended that such passages be read allegorically with an eye to "deeper" meaning. In the seventeenth century, philosopher Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677) wrote his Theologico-Political Treatise, a groundbreaking work that argued cogently that scripture is not the Word of God, but a thoroughly fallible human document. The only deep truth it contains is the command to love one's neighbors. Needless to say, Spinoza's horrified contemporaries regarded the book as a document "forged in hell" and demanded its proscription.

In the next century, Tom Paine (1737-1809) went a step further in The Age of Reason, arguing that much of scripture is not only absurd but evil. When we consider the massacres, tortures, and relentless vindictiveness of so much of scripture, it is more reasonable to see it as the word of a demon rather than the Word of God. In the next century, the great freethinking controversialists such as Robert Ingersoll, Charles Bradlaugh, and T.H. Huxley mopped the floor with the defenders of biblical literalism.

Since the nineteenth century, the higher critical study of the Bible has shown in detail the complexities and uncertainties of the Bible's composition, authorship, reliability, and messages. The most recent scholarship, summarizing the fictional and legendary origins of the story of Jesus, is Elaine Pagels' Miracles and Wonder: The Historical Mystery of Jesus (2025). Pagels is not a radical; such conclusions have been mainstream for biblical studies for many years. Such studies are devastating. Christianity rests upon specific historical claims. As Paul put it (Corinthians 15:14), "And if Christ be not risen, then is our preaching vain, and your faith is also vain." If certain things did not happen, then Christianity is false. Period.*

Of course, fundamentalist Christians reject all such analyses and insist upon the inerrancy of scripture. It happened just like they learned in Sunday School. They have to tie themselves into moral and hermeneutical knots to think so, and their opposition to biblical scholarship, like their opposition to cosmology and biology, only results in demonstrating the intellectual and moral bankruptcy of fundamentalism.

Note: If anybody wants overwhelming (and often highly entertaining) evidence of the fallibility (and, often, just plain God-awfulness) of scripture, The Skeptic's Bible (2012) annotated by Steve Wells is most enthusiastically recommended.

2. Religion provides no basis for ethics

Religious apologists often insist that religion provides the only legitimate basis for ethics. They echo the lament attributed to Fyodor Dostoevsky: "If God does not exist, then everything is permitted." In other words, the only possible basis for regarding some things as objectively morally good and others as objectively morally bad is to posit the existence of God. All naturalism can do is tell us that we do find certain things morally reprehensible, but cannot explain why they are reprehensible. In another earlier essay/Letter ("Why Should an Atheist be Moral?" 9/11/24) I argued for a secular basis of ethics in neo-Aristotelian naturalism. Again, I will not repeat arguments. Here I will say why ethics cannot be based on religion. Actually, for the sake of focus, I will say why ethics cannot be based upon the claims of Christianity.

Just what are the claims of Christianity? Well, of course, we have explicit commands from the scripture recognized as authoritative by Christians. For instance, Exodus 22: 18 says "Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live." Deuteronomy 21: 18-21 says that if a son is rebellious and eats and drinks too much, he should be handed over to the elders of the city who will stone him to death. Exodus 35: 2 says that anyone who works on the Sabbath shall be put to death. Leviticus 15: 19-24 says that a man should have no contact with a woman during her period of "menstrual uncleanness." Leviticus 11:10 says that the eating of shellfish is an abomination (no shrimp or oysters). In I Samuel chapter 15, The Lord, still angry over what the Amalekites did to Israel hundreds of years before, orders Saul to kill all of their descendants (verse 3) "Now go and smite Amalek, and utterly destroy all that they have, and spare them not; slay both man and woman, infant and suckling, ox and sheep, camel and ass." So, God's commands include the occasional genocide.

Am I taking a cheap shot? Village atheist sneering? Aren't Christians exempt from the nitpicky rules of the Torah? For instance, can't a Christian enjoy a plate of oysters? Actually, things are not so simple. In Oklahoma, the Ten Commandments are required to be included in public school curriculum. Here in Baja Oklahoma, where I live, the state senate has just passed a bill to require displays of the Commandments in Texas schools. So, the Decalogue must still be considered authoritative for the conservative Christian who pass these laws. It therefore needs to be made clear just which Old Testament commands are binding on current Christians and which ones are not, and this is a further complication.

Of course, generations of apologists have exerted vast labors to address the "difficulties" of scripture, arguing either (a) these verses do not mean what they say, or (b) the verses do mean what they say, and the commandments are actually good (e.g., shellfish go bad in a hot climate.).** The problem is that the "solutions" to these "difficulties" are often worse than the original "difficulties." Here is a well-known case in point: There are two accounts of how Judas Iscariot met his death. Matthew 27: 3-8 says that Judas hanged himself. Acts 1:18-19 (written by Luke) says that he fell down and disemboweled himself. Apologists have attempted to reconcile these two accounts by saying that he hanged himself and then the rope broke and he fell down and eviscerated himself. No comment.

Even if, as my Christian friends argue, some of the more hair-raising passages can be interpreted more benignly, you would think that God would have been a bit more careful about how he said things, knowing people's propensity to misinterpret. For instance, Apostle Paul says things that prima facie are stunningly sexist. For instance, supposedly speaking with the authority of the Holy Spirit, Paul says in I Corinthians 14:34 and I Timothy 2: 11-12 that in church women should shut up and not have any authority over men. Did Paul mean it? The Southern Baptists sure think so. They do not allow women pastors. If they are wrong, maybe God should have made his intentions somewhat clearer.

So, basing morality upon explicit scriptural commandments seems dicey. At the very least, a great deal of complex, convoluted—and controversial--interpretation and exegesis will be required to get clear on just what is commanded. The basis for ethics should be something simpler and clearer.

However, even if some definitive account of just what God commands could be produced, such commands cannot, in principle, serve as a basis for ethics. The reason is dead simple. Are those commands good? Does it make sense to ask whether God's commands are good? For instance, was God's command to massacre the Amalekites good? Surely, these are meaningful questions. If God's commands are good, then there must be a standard of goodness whereby they can be judged good. In that case, though, obviously God's commands are themselves held to a standard and therefore cannot constitute that standard.

If it is replied that God's commands, by definition, constitute the standard of goodness just as the laws constitute the standard of legality, then, to say that God's commands are good would be just as vacuous as saying that the laws are legal. True but uninformative. We would be left with no reason why those commands deserve our respect.

If it is replied that God's nature is essentially good, so that goodness is not something separate from and superior to God (i.e., God's commands are good because they conform to his essentially good nature), it still has to be meaningful to ask in what God's essential goodness consists. That is, what are the qualities that make God's nature good, as opposed to evil or neutral? If such qualities cannot be identified, then it makes no more sense to say that God is good than that God is evil or neutral. If these qualities can be identified—say benevolence, mercifulness, truthfulness, etc.—then there seems to be no reason such qualities cannot be articulated without mentioning God. In that case, ethics can be based on the identified qualities of essential goodness and reference to God should just be dropped as irrelevant. Further, we may certainly still ask whether the explicit commandments recorded in scripture (massacres, stonings, genocides, etc.) are consistent with the purported supreme goodness of God's nature—on any reasonable construal of the meaning of "supreme goodness." Short answer: Ha Ha! Seriously?!? No way.

Finally, some will argue that God is necessary for morality because there will be no ultimate motivation to be good if there is no fear of postmortem punishment. If a bad guy is smart and/or lucky, he can escape punishment by earthly authorities. Many, many crimes, including some of the most notorious, have never been solved, at least, not during the lifetime of the perpetrator. Around the world, many thousands of young women annually disappear without a trace, and no one is ever held responsible. Crime often does pay. Many who have lived lives of treachery, lies, and cruelty die old, fat, and rich, laughing at their victims. C.S. Lewis defends the idea of hell by saying that such persons should not go into eternity having the last laugh. Postmortem retribution would plant the flag of righteousness in them and force them to admit that they were wrong. Immanuel Kant held that it is a moral tragedy if there is no God, because without a God there is no guarantee that the good will be rewarded and that the evil will be punished. For morality to be taken seriously, therefore, we should posit a God who will hold sinners responsible.

My first response is to ask whether anybody—anybody—has ever really refrained from doing something wrong out of fear of hell. I honestly doubt it. Hell is never for you. Hell is for those bad people. You know: Liberals, feminists, university professors, LGBTQ people, evolutionists, atheists, and Democrats. People with a very lively belief in hell have committed the most outrageous atrocities. Christian nationalists—hell-believers to a man and woman—are the worst people in the country.

More basically, we ought to see the world as morally tragic. With both eyes open we should face the fact that if the good are to be protected and the evil brought to justice, WE have to do it. WE have to protect the weak from the strong. WE have to pass the laws to keep the avaricious from taking all we have. WE have to defend freedom against tyranny. WE have to expose the lies and subterfuges the unscrupulous use to justify their depredations. God will not do it for us.

WE have to do it.

*Tom Holland in In the Shadow of the Sword shows that in addition to the problem of the historical Jesus, there is a problem of the historical Mohammed. Richard Carrier tells me (private communication) that there is also a problem of the historical Buddha.

**Bullshit. The Native Americans who lived in a hot climate on the coast of Georgia ate so many millions of oysters that the mounds of their shells are twelve feet high.

Note: Anyone may copy and publish what I or my guests write, provided proper credit is given, that it’s not done for commercial purposes, that I am notified of the copying (you can just leave a comment saying where the copy is being published), and provided that what we write is not quoted out of context or distorted.

Thanks again for reading Letters … . Subscribe for free (always) to receive new posts and support my work.

Excellent article!

https://churchandstate.org.uk/2025/05/reasons-for-unbelief/