SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF PSEUDOSCIENCE

Living (if you call this "living") in an era when the highest government official in charge of public health is a notorious crank, and when science is under attack across many fronts, it is important to ask what distinguishes genuine from fake science. This is not a mere academic exercise in definition. Lives are at stake. Junk science kills. A society that pursues theories not because of their rational credentials but because they serve an ideological agenda, is one doomed to great suffering. The most notorious example was the genetic theories of Trofim Lysenko which were scientifically worthless but congenial to Marxist/Leninist dogma. Stalin therefore promoted Lysenkoism and sent real geneticists to starve in the Gulag. When traditional agricultural practices were replaced by Lysenkoist claptrap, the crops, perversely, refused to yield.

Trofim Lysenko (1898-1976), right, examines wheat-ear

Why, then, since science works and pseudoscience does not, would any sane, rational person pursue pseudoscience? The key terms here are "sane" and "rational." We can dig a bit deeper into the motivations of pseudoscientists. Some, obviously, have an unshakeable devotion to an ideology, a creed that admits of no contradiction or deviation. Religious fundamentalists are obvious examples. If the Book of Genesis must be taken as inerrant, then the Earth can be no more than six to ten thousand years old (which is off by six orders of magnitude). Whole sciences must be rejected in that case and replaced with the bizarre fantasies of young earth creationism.

Political ideologies—and not just those of the right—can also serve as science killers. I have known feminists who were just as dogmatic as any Bible-beating fundies, and some have told stories as bizarre as creationism. A few decades back a subsect of feminists promoted the pseudo-archaeological myth that early Europeans were peaceful worshippers of the Mother Goddess and ruled by wise matriarchs until men (Men!) ruined everything with warfare, hierarchies, and sky gods.

Then there are the psychological motivations. Many advocates of pseudoscience, like the proponents of conspiracy theories, are sure that everything you know is wrong and that, unlike you, they are smart enough to see through it. In reality, they are too dumb to realize how dumb they are. They get a thrill from thinking that they know more than the "elites" that have looked down on them—all those smarty pants scientists, know-it-all doctors, and eggheaded professors. Medical professionals treating COVID patients have found themselves angrily confronted by patients' families when they refused to prescribe ivermectin or hydroxychloroquine. They think that some halfwit on the internet knows more than the doctors and scientists.

So we know the motivation for pseudoscience; how do we recognize it? Philosophers have sought "demarcation criteria," a simple, reliable standard to distinguish science from non-science. A popular candidate, drawing on the philosophy of Karl Popper, is falsifiability. Popper argued that the distinguishing mark of genuinely scientific claims is that they are falsifiable, that is, that they can be shown wrong. All genuinely scientific theories face the tribunal of experience. That is, they must be susceptible to refutation by the facts. Einstein predicted that light would be bent by massive bodies. He was right, but the important point is that he could have been wrong. His prediction might not have been borne out by observation. By contrast, said Popper, pseudoscientific theories such as Marxism or Freudianism were impervious to empirical refutation. The theories were endowed with unlimited flexibility that allowed them to accommodate any set of facts. Therefore, unlike Einstein's theories, they were not scientific.

Karl Popper (1902-1994)

Popper was certainly correct that a theory that does not have to answer to the facts, that is, one that has no empirical content, cannot be a scientific theory. However, as a general demarcation criterion, falsifiability is inadequate. The basic problem is how to set up the criterion so that it is neither too strict nor too lenient. If you make it too lenient, then some clearly unscientific theories, like creationism, might pass the criterion. Even the silliest theory could probably come up with something, however farfetched, that, in principle, would falsify it.

On the other hand, if you make it too strict, then some theories that are unquestionably scientific might get ruled out. In practice, scientists often do not reject an otherwise successful theory because it has some anomalies. Famously, Newtonian celestial mechanics could not account for irregularities in the orbit of Mercury ("the precession of the perihelion"), but Newton was not dethroned (until relativity theory explained the irregularity). Indeed, as the philosopher/scientist Pierre Duhem noted, contrary evidence is often handled not by rejection of the theory per se but by placing the blame on an "auxiliary hypothesis." Only when anomalies pile up, and there is no reasonable means of handling them, does a theory enter crisis mode, and even then it is often not fully abandoned until a new and better theory is formulated.

Pierre Duhem (1861-1916)

If no single, one-size-fits-all demarcation criterion can be found, does that mean that we have to give up trying to distinguish between science and pseudoscience? I don't think so. I think that identifying pseudoscience is a lot like diagnosing disease. Generally, no single symptom is diagnostic. Rather, doctors look for an ensemble of symptoms that, taken together, can point to a diagnosis. Judging a theory must be holistic; that is, you have to consider both its strengths and weaknesses. New theories will often have considerable, even glaring weaknesses, but if they also have notable strengths, they can be recognized as promising despite their lacunae. On the other hand, if a theory violates the norms of good science, and possesses no sufficient virtues in compensation, then it at least counts as bad science. If the violations are egregious enough and virtues utterly lacking, attaching the label "pseudoscience" is justifiable.

I therefore offer signs and symptoms of pseudoscience. They cannot be applied algorithmically, but when the failures are sufficiently numerous or severe, a rational judgement can be made.

1) Poor (or no) explanations.

Why are there birds? Paleontology tells a fascinating story. Nineteenth century anatomist T.H. Huxley noted the close skeletal similarities between birds and small theropod dinosaurs. More recent fossil discoveries, including feathered dinosaurs have greatly strengthened that connection. Most paleontologists now agree that birds are evolutionarily modified dinosaurs. Evolution is a process that is deeply understood and which provides the explanatory framework for understanding the diversity of life on earth. So fundamental is evolution that Theodosius Dobzhansky (1900-1975), one of the leading geneticists of the twentieth century said, "nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution."

How does creationism account for birds? Genesis 1:21 says that God created birds on the fifth day of creation. How did it happen? Presumably, God said, "Let there be birds!" and POOF! The air was full of birds! Nice picture, but this is not an explanation. Saying that a supernatural being wielding occult powers created birds with a miraculous speech act provides maybe an imaginative picture, kind of like a cartoon version of Michelangelo. However, the intellect wants understanding, not a picture. How did it happen? What was the process? How do you make a bird? The Genesis "answer" seems to be "God did it, so shut up!"

Mythological accounts, like Genesis, satisfied humans for many centuries, but we have since learned to ask questions that myth cannot address. Pseudoscience offers scenarios but no real explanations. Insofar as they cite causal factors, they are vague, mysterious, and inscrutable. How do "astrological influences" supposedly determine your fate? As Carl Sagan pointed out, the doctor delivering the baby exerts more gravitational influence on the newborn than the planet Jupiter.

2) Employment of ad hoc hypotheses.

An ad hoc hypothesis is one adduced to save a cherished claim from falsification by contrary evidence. There is no independent basis for the ad hoc hypothesis. It serves only to insulate a claim that someone very much wants to be true. Pseudoscientific theories tend to surround themselves with a bodyguard of ad hoc hypotheses that serve to protect the pet theory from pesky evidence.

Remember Uri Geller? He was the Israeli "psychic" who claimed to be able to perform stunts like bending keys with the "power of his mind." Actually, he was just a cheap, two-bit stage magician. Skeptical magician James Randi, who loved exposing the mountebanks (and was very good at it) demonstrated his key bending abilities using stage magic trickery. When skeptical magicians such as Randi were present, those who could see through Geller's tricks, his "powers" mysteriously vanished. Geller blamed it on "bad vibes" supposedly emitted by the skeptical observers, and that such "vibes" interfered with the exercise of his real powers. Of course, there was no evidence of "vibes" emanating from Randi; the whole conjecture was an ad hoc excuse.

3. Confirmation by anecdote.

Everybody knows somebody that knows somebody that had something weird happen to them. We have all heard ghost stories. The African-American people my dad knew while growing up in rural Georgia had a rich trove of such stories. Here is one that got passed down to me: Old James had a brother that drank himself to death. As James would be riding in his wagon with his own bottle along a dark country road, he would hear footsteps behind him. Icy fingers would touch his neck and a guttural voice, unmistakably his brother's, would demand "Whiskey. Whiskey. Whiskey." James would pour some liquor onto the ground, and he could hear his brother's ghost lapping it up. Boo!

Anecdotes are often vivid. That gives them an edge over carefully compiled data. A scumbag illegally entered from Venezuela murdering Laken Riley is far more vivid than thorough compilations of data showing that first-generation immigrants, whether they entered legally or not, have a lower crime rate than native-born Americans. I have a cousin who says that he and his wife had bad experiences after getting COVID shots, so they refuse to get any more. They had bad cases of COVID a couple of months ago. Anti-Vaxx activists, like the current head of Health and Human Services, glom onto such instances and ignore the overwhelming data supporting the safety and efficacy of the vaccines.

Purveyors of quack cures have long appealed to testimonies, from the traveling snake oil hawkers of the nineteenth century to today's feel-good holistic practitioners. Getting testimonies for worthless therapies is easy. I have heard it said that if someone is doing poorly, and they take a dose of something and then feel better, no power on earth can convince them that the dose was not responsible for their improvement. Yet diseases, even ultimately fatal ones, have ups and downs, good days and bad days. In the bad old days when tuberculosis claimed many, there were many hyped but worthless treatments. I saw a facsimile of an advertisement from circa 1890 that had enthusiastic testimonies in favor of Nature's Cure for tuberculosis. Beneath each testimony someone had drily recorded the death date, from tuberculosis, for each testifier.

4) Junk evidence.

Confirmation bias always lurks, ever ready to pounce and kill good reasoning. If you begin with the conviction that extraterrestrials visited the earth in the human past and present, you can find "evidence" everywhere. Ancient drawings and sculptures, if looked at with an imaginative eye, could be construed as recording the encounters of ancient people with technologically advanced aliens. Erich von Däniken, in his 1970 bestseller Chariots of the Gods? includes many depictions of sculptures and drawings from ancient sites which, if looked at with a certain set of expectations, could be taken as representing aliens or spaceships.

Further, many sane, intelligent people of the present day will report encounters with aliens and even abductions. On the old Tonight Show with Johnny Carson (Deeply missed. Sigh.) Carson interviewed popular author Whitley Strieber who had just written a book claiming to have been abducted by aliens from his New Hampshire farmhouse and taken on board a spacecraft. Strieber appeared intelligent and sane, and many other seemingly plausible people have reported similar encounters. So have we been visited and are we being visited?

However, you have to consider all of the available evidence, not just the fun part. Archaeologists have long known of other evidence that licenses much more plausible and mundane explanations of the artifacts. Scientists, unlike pseudoscientists, recognize that you have to look at the total evidence, not just the bits that appear to support your preconceived notions. This is why control groups figure so prominently in scientific testing. The disconfirming evidence has to be given the same chance as the confirming evidence.

As for the "abductions," Carson at the time asked Strieber if it might not have been a dream, and Strieber could only reply that it did not seem to be a dream. However, hypnogogic and hypnopompic hallucinations are quite well known phenomena. They can be quite frightening, with a sense of being paralyzed in the presence of an inhuman evil. Henry Fuseli's 1781 painting The Nightmare probably depicts such a hallucination, with an evil incubus sitting on the chest of a sleeping woman:

Conclusion:

Science is a precious possession, but like all human creations it can be destroyed by malice. Our government today is in the hands of aggressively ignorant barbarians who hate science and scientists. They must be fought. Like liberty, the price of rationality is eternal vigilance.

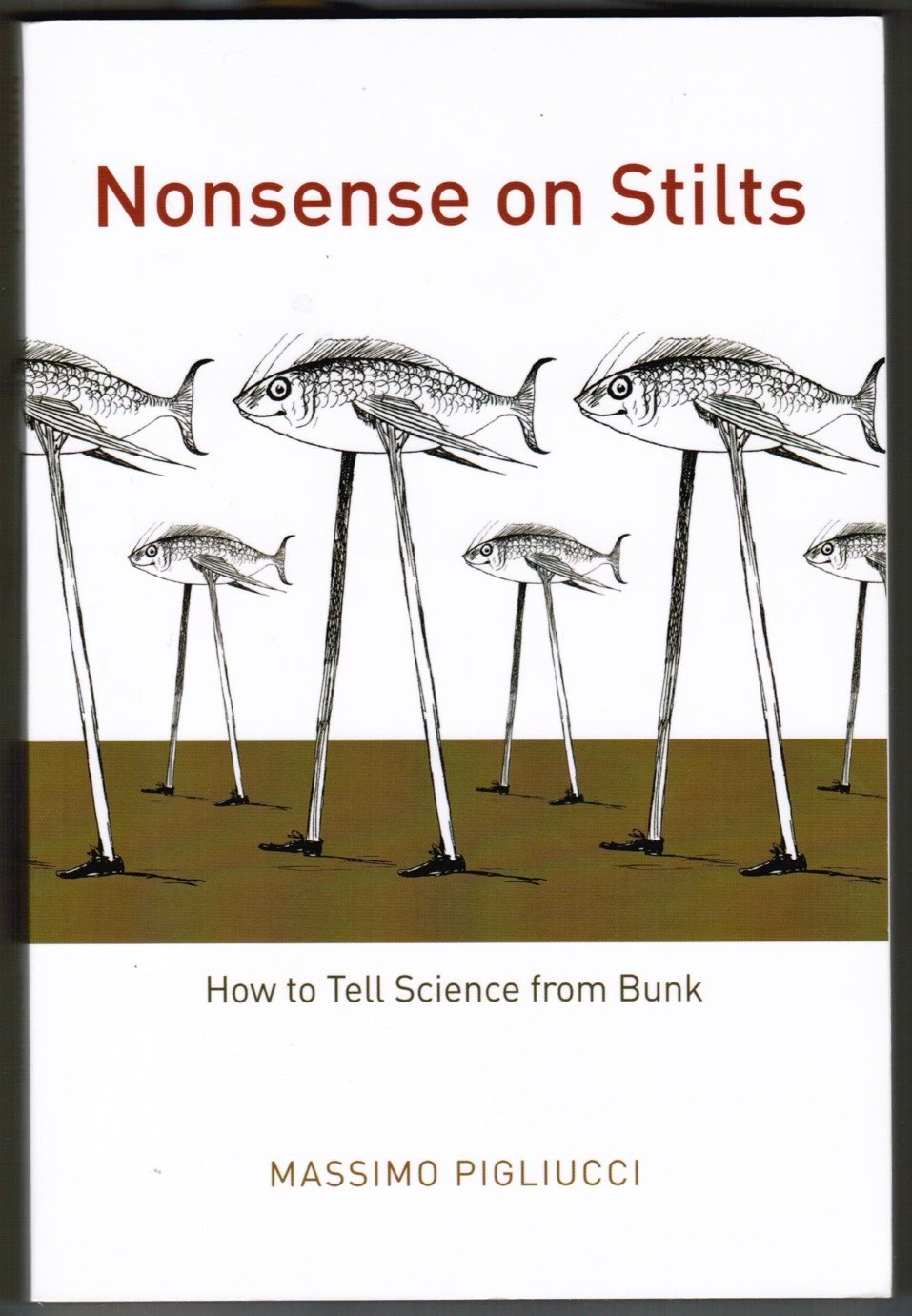

For an interesting read on the subject, try this 2010 book—

Note: Anyone may copy and publish what I or my guests write, provided proper credit is given, that it’s not done for commercial purposes, that I am notified of the copying (you can just leave a comment saying where the copy is being published), and provided that what we write is not quoted out of context or distorted.

Thanks again for reading Letters … . Subscribe for free (always) to receive new posts and support my work.

Thanks for the plug! A second, more recent edition, of that book exists: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/N/bo28300772.html

I met Uri Geller in 1973 or 1974 while I was attending Suffolk County Community College in Selden, NY. He gave one of his demonstrations of mental ability, and then said he would drive someone's car while blindfolded. He insisted that it be a large, six-passenger car. While we waited for the car to arrive, Uri asked if anyone had an old key with them. The guy standing to my left produced an old, brass or bronze key about two inches long. It was very thick as well. Mr. Geller took it between his palms and rubbed it back and forth. I was standing with my right shoulder up against his left shoulder, and asked him to put the key down flat on my outstreched palm; which he did. He placed his index finger on the middle of the key, saying it would take longer this way. There were several of us students grouped around staring at his finger pushing the key down on my palm. It began to bend, slowly at first, then it got to about a 45 degreee bend and he removed his finger. I took the key and tried to straighten it. I pulled on it as hard as I could, making indentations in my fingers. I then gave it back to the guy who owned it. He also tried to straighten it, unsuccessfully. It continued to bend as he held it until it was bent more than 90 degrees. The guy with the Grand Prix showed up, and another friend of mine jumped in the back seat, sliding over to sit behind the driver seat. Uri Geller got behind the wheel and the car's owner and his friends got in. There were six people in the car, including Uri Geller and my friend sitting behind him. It was winter; everyone had on heavy coats. My friend had a detachable hood on his coat; which he took off and tied backwards on Uri Geller's face. It was thick wool material lined with faux fur. They slowly drove through the parking lot, to the exit. They turned onto the highway and disappeared from our view. They returned 10 or 15 minutes later, and my friend told what happened. He said there was complete silence in the car as they drove. Mr. Geller made several lane changes, passing a couple of cars before returning to his lane. Then he made a u-turn, waited for several cars to go by, then got back on the highway and returned to the campus. He stopped by the entrance and pulled over to take off the hood covering his face. He said he could "feel" when to slow or speed up or turn by what the occupants of the car were feeling. He said it wasn't like he was seeing through their eyes; he was experiencing their emotions and intentions. That's why he wanted a big car to hold more people.

So, could one of the people in the car have been helping him by touching his leg or some other way? Possibly. We were all aquainted with one another as students at the college. I knew two of them more as friends, as well. We all said we never met Uri Geller before. There was nothing unusual about the key other than it was thicker than most I had seen before. I don't why Uri Geller had trouble demonstrating his ability on the Johnny Carson show or elsewhere. Maybe there is some form of electrical energy we all radiate. The so-called "vibes" people speak about. I'm agnostic about the whole thing. This story of mine is a one-time thing with no scientific controlls or protocols. My opinion is that Uri Geller has some kind of power he cannot always control that the average human does not posess.