Did President George Washington Pray that We Should Remember that the USA is a Christian Nation?

16 June 2023--Friday Freethought Perennial #20

About the Friday Freethought Perennials (FFPs) in general: This subset of my Letters is to answer questions, nearly always already answered by me and by many others but posed again and again—over many years and in many places—on freethought, atheism, secular humanism, secularism/church-state/”This is a Christian Nation,” and similar topics. These answers are mostly not intended to be original analyses, breaths of fresh air, so much as just putting a whole series of things on the record (I’d say “forever,” except I know better). One source for many of these answers is the 2012 Prometheus Books book by me and my son (Michael E. Buckner), In Freedom We Trust: An Atheist Guide to Religious Liberty (abbreviation: IFWT). It’s available in many libraries and pretty readily in the used book after-market. I’ll cite writings of others that answer these things in more depth if I’m aware of them when I post these.

Did George Washington Pray that We Should Remember that the USA is a Christian Nation?

Ed Buckner

Did George Washington pray that we should remember that the United States is a Christian nation?

Nope.

And the prayer sometimes identified as somehow suggesting that he did (as strongly implied this week by Rev. Dr. Richard G. Lee of Cummings, GA, for example) did not even mention the “United States,” despite Lee’s misquoting it as doing so.

And it omitted any allusion to the United States with good reason—when Washington sent around his June 1783 circular letter, the government of the United States had not yet been invented, nor in fact had the United States itself. That may seem like a mistake or a mere technicality, but it’s far more than that. See—

https://www.mountvernon.org/the-estate-gardens/the-tombs/george-washingtons-prayer-for-his-country/

Commander in Chief of the Continental Army Washington—his title in 1783—was using religion (whether or not he was himself religious—there’s evidence both ways on that) for a political purpose. He was shoring up unity and a developing sense of national identity among thirteen different States.

Timing matters. We were operating then under the Articles of Confederation, not under the U.S. Constitution, and the Constitutional Convention that established the United States and our government was still four years into the future—and it would be longer than that before the government it set up actually began. The first George Washington term as President started on 4 March 1789, the date set by the Congress of the Confederation for the beginning of operations of the federal government under the new U.S. Constitution.

That constitution could have invoked divine authority—nearly all human governments in the history of the West up until then, did that. The Constitution could have asserted Christianity as its basis, at least in part—as many of the States under the Articles of Confederation had. The new constitution could have established a Christian government—after all, as Rev. Lee of Cummings rightly pointed out, the separate thirteen governments mostly did deny religious liberty in that way. Lee gave us what Delaware enacted, for example:

If you wanted to hold public office in Delaware (as in many of the new States) in the 1780s you had to be—or at least to say you were—a Christian. Christians could exercise religious freedom—but only Christians could.

Many things were taken for granted, accepted by most Americans—by most Westerners—then as just “obviously true”—

that whites were better than non-whites

that women could not be as effective as men as citizens and should defer to men

that Native Americans were savages and needed to be moved along (or worse)

that God installed kings on their thrones

that religiosity and morality were causally linked and, in many of the new States,

that Christianity was based on divine truth but needed governmental protection.

But the times were changing, and not just because patriots had overthrown the royal power in the 1776-1781 Revolutionary War. The framers of the U.S. Constitution meeting in Philadelphia in 1787 had the examples of State charters right at their fingertips and could easily have created the new federal government along similar lines.

But they deliberately did not.

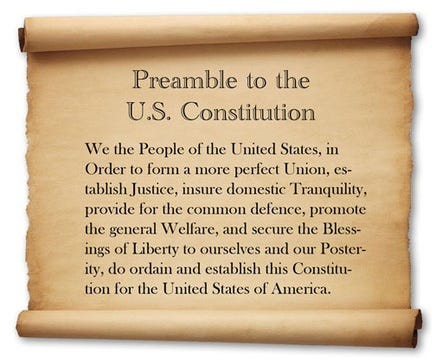

With the opening six words of the Preamble, the authority invoked for the governing charter was plainly and exclusively secular:

“We the People of the United States”—not God, not Christianity, not State governments, not ancient texts—we the people—”do ordain and establish… .” This was assuredly not Christian, but it was also in no way anti-Christian.

And less than a decade later (in June 1797), that secular nature was officially and powerfully reconfirmed when the U.S. Senate unanimously ratified and President John Adams signed and proclaimed a treaty agreed to during Washington’s last months in office as President that declared that

“the government of the United States is not in any sense founded on the Christian religion.”

What about the government of Delaware, etc.? Those States kept their religious establishments or preferences and many maintained slavery and all kept women as second-class citizens, etc.—for a while. But such “States Rights” were seriously curtailed in the 1860s and beyond—through war and constitutional amendments—more about that next week.

Trivia question to ponder in the meantime: what U.S. State was the last one to have an official established religion and when was it disestablished?

Note: Anyone may copy and publish what I or my guests write, provided proper credit is given, that it’s not done for commercial purposes, that I am notified of the copying (you can just leave a comment saying where the copy is being published), and provided that what any of us write is not quoted out of context or distorted.

Anyone watching the recent coronation of Charles III could hardly fail to notice the numerous--almost nonstop--invocations of Christianity, God, and Christ. This demonstrated, more clearly than any history book could, the absolute conviction that British monarchs ruled "dei gratia." And, of course, they were hardly unique in this. Rulers back to Hammurabi had been at pains to emphasize that their authority came from God or the gods. Given this context, the Founders' omission of such any such appeals was glaringly obvious, indeed shocking. Conservatives were appalled at the time, and they still are. That is why they have to invent so many lies.

Rereading what I wrote here, I realize I might be misinterpreted. The phrase "United States of America" had certainly been used before the Constitution was adopted. But after 1787-1789, the phrase had a substantially different meaning. The loose alliance under the Articles of Confederation had now become a united nation--one governed under a secular government.