Old But New(ish) Variation of Friday Freethought Perennials Using Old Stuff--Quotations (II-2 of VI) (Jefferson, part 2)

Friday Freethought Perennial 1 November 2024

About the Friday Freethought Perennials in general: This subset of my blog is to answer questions, nearly always already answered by me and by many others but posed again and again—over many years and in many places—on freethought, atheism, secular humanism, secularism/church-state/”This is a Christian Nation,” and similar topics. These answers are mostly not intended to be original analyses, breaths of fresh air, so much as just putting a whole series of things on the record (I’d say “forever,” except I know better). One source for many of these answers is the 2012 Prometheus Books book by me and my son (Michael E. Buckner), In Freedom We Trust: An Atheist Guide to Religious Liberty. It’s available in many libraries and pretty readily in the used book after-market. I’ll cite writings of others that answer these things in more depth if I’m aware of them when I post these.

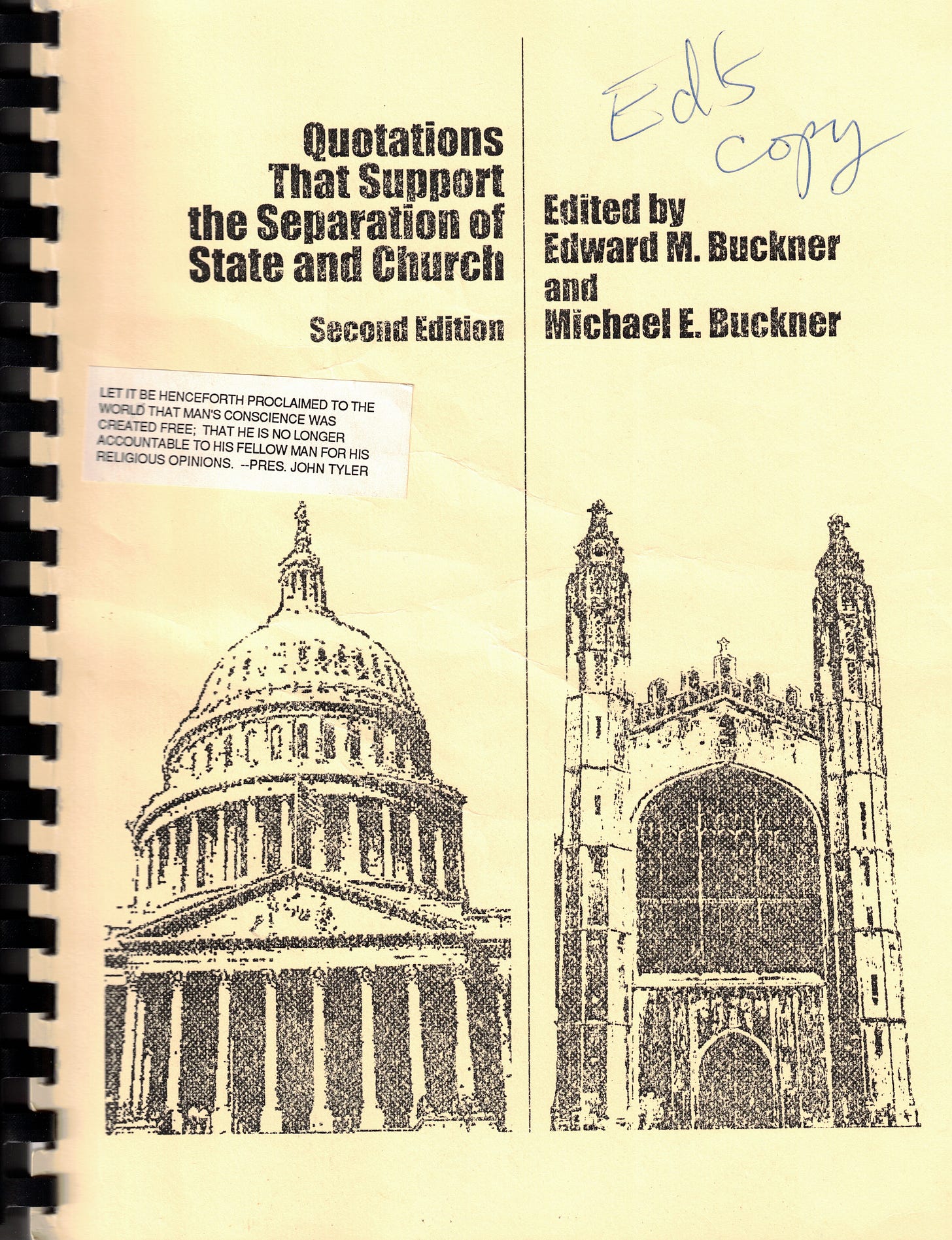

Today’s (and the ones that follow on future [not necessarily consecutive] Fridays) are from an older project my son Michael and I started over 30 years ago. The resulting book of Quotations That Support . . . ., published by the Atlanta Freethought Society, is no longer available (one online bookseller claims to have a copy that he’ll sell you for over $100!), though at least some of this has been published online before.

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826; author, Declaration of Independence and the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom;3rd U.S. President, 1801-1809)

Image is of a Jefferson nickel in the process of being edited because “FREEDOM” needs to be inserted between “IN” and “WE TRUST” to be properly Jeffersonian.

The quotations presented here, drawn in every case directly from the most original source available to the editors, should prove useful to those arguing, in a variety of ways or contexts, in favor of separation of church and state, religious freedom, and the rights of religious or, especially, irreligious minorities.

Quotations supporting atheism, deism, or unorthodox religious views are included to the extent that they might be useful in debating against those who argue that the United States was established as a Christian nation or that the “founding fathers” would have accepted government support or enforcement of any religious orthodoxy.

Not all the quotations are from humanists or freethinkers nor even from people committed to complete separation of church and state, but the quotations are all, as far as we can determine, genuine, accurate, and not distorted by being taken out of context.

These postings are of course primarily as reference rather than reading material and anyone who wants to save and use them can certainly do that. The quotations I’m re-publishing on a number of different dates here are arranged in six major parts, with some subsections within those.:

I. U.S. Constitution, U.S. Treaty, State Constitutions (two weeks ago)

II. Founding Fathers—National Leaders and Thinkers from the Revolutionary Era (second—part two of the two including material on Thomas Jefferson—of several subparts today)

III. Presidents (and Other National Political Leaders) Since the Revolutionary Era

IV. U.S. Supreme Court and Other Judicial Rulings

V. Other Famous Americans

VI. Foreign Sources

Quotations are arranged in approximate order of historical significance in Parts I and II, with separate subsections in Part II for major leaders (Jefferson, Madison, Washington, John Adams, Franklin, and Paine) followed by a subsection of others from the era, then by a subsection of historians and others about the era in general. Parts III though VI are arranged in approximate chronological order (except with all material from or about a particular source kept together) within each part.

II-2. Founding Fathers (more Jefferson)

National Leaders & Thinkers from the Revolutionary Era

Thomas Jefferson [There is so much material on and by Jefferson that it takes two posts just to cover the Jefferson material—this is the second of those two.]

…If we did a good act merely from the love of God and a belief that it is pleasing to Him, whence arises the morality of the Atheist? It is idle to say, as some do, that no such thing exists. We have the same evidence of the fact as of most of those we act on, to wit: their own affirmations, and their reasonings in support of them. I have observed, indeed, generally, that while in Protestant countries the defections from the Platonic Christianity of the priests is to Deism, in Catholic countries they are to Atheism. Diderot, D’Alembert, D’Holbach, Condorcet, are known to have been among the most virtuous of men. Their virtue, then, must have had some other foundation than love of God.

—Thomas Jefferson, letter to Thomas Law, June 13, 1814. From Adrienne Koch, ed., The American Enlightenment: The Shaping of the American Experiment and a Free Society, New York: George Braziller, 1965, p. 358.

Across the ages, clergy have been interested [according to Jefferson] not in truth but only in wealth and power; when rational people have had difficulty swallowing “their impious heresies,” then the clergy have, with the help of the state, forced “them down their throats.” Five years later, he [Jefferson] wrote of “this loathsome combination of church and state” that for so many centuries reduced human beings to “dupes and drudges.”

—Edwin S. Gaustad, Faith of Our Fathers: Religion and the New Nation, San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1987, p. 47. According to Gaustad, the first quotes are from a letter from Jefferson to William Baldwin, January 19, 1810; the second source is a letter from Jefferson to Charles Clay, January 29, 1815.

A professorship of Theology should have no place in our institution [the University of Virginia].

—Thomas Jefferson, letter to Thomas Cooper, October 7, 1814. From Gorton Carruth and Eugene Ehrlich, eds., The Harper Book of American Quotations, New York: Harper & Row, 1988, p. 492.

I have ever judged of the religion of others by their lives.… It is in our lives, and not from our words, that our religion must be read. By the same test the world must judge me. But this does not satisfy the priesthood. They must have a positive, a declared assent to all their interested absurdities. My opinion is that there would never have been an infidel, if there had never been a priest. The artificial structures they have built on the purest of all moral systems, for the purpose of deriving from it pence and power, revolt those who think for themselves, and who read in that system only what is really there.

—Thomas Jefferson, letter to Mrs. M. Harrison Smith. M. Harrison;, August 6, 1816. From Gorton Carruth and Eugene Ehrlich, eds., The Harper Book of American Quotations, New York: Harper & Row, 1988, p. 492.

“I never told my own religion, nor scrutinized that of another,” Thomas Jefferson once remarked, adding that he had “ever judged” the religion of others by their lives “rather than their” words.

—Richard B. Morris.;, Seven Who Shaped Our Destiny: The Founding Fathers as Revolutionaries, Harper & Row, 1973, p. 269. The Jefferson quote is from his letter to Mrs. M. Harrison Smith., 1816.

He [Jefferson] rejoiced with John Adams when the Congregational church was finally disestablished in Connecticut in 1818; welcoming “the resurrection of Connecticut to light and liberty, Jefferson congratulated Adams “that this den of priesthood is at length broken up, and that a protestant popedom is no longer to disgrace American history and character.”

—Edwin S. Gaustad, Faith of Our Fathers: Religion and the New Nation, San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1987, p. 49.)

But the greatest of all reformers of the depraved religion of his own country, was Jesus of Nazareth. Abstracting what is really his from the rubbish in which it is buried, easily distinguished by its lustre from the dross of his biographers, and as separable from that as the diamond from the dunghill, we have the outlines of a system of the most sublime morality which has ever fallen from the lips of man.… The establishment of the innocent and genuine character of this benevolent morality, and the rescuing if from the imputation of imposture, which has resulted from artificial systems, invented by ultra-Christian sects*…is a most desirable object. [Jefferson’s footnote:] *The immaculate conception of Jesus, his deification, the creation of the world by him, his miraculous powers, his resurrection and visible ascension, his corporeal presence in the Eucharist, the Trinity; original sin, atonement, regeneration, election, orders of the Hierarchy, etc.

—T.J. (Thomas Jefferson, letter to William Short, October 31, 1819. From George Seldes, ed., The Great Quotations, Secaucus, New Jersey: Citadel Press, 1983, p. 364.)

It is not to be understood that I am with him (Jesus Christ) in all his doctrines. I am a Materialist; he takes the side of Spiritualism; he preaches the efficacy of repentance toward forgiveness of sin; I require a counterpoise of good works to redeem it….

Among the sayings and discourses imputed to him by his biographers, I find many passages of fine imagination, correct morality, and of the most lovely benevolence; and others, again, of so much ignorance, so much absurdity, so much untruth, charlatanism and imposture, as to pronounce it impossible that such contradictions should have proceeded from the same being. I separate, therefore, the gold from the dross; restore to him the former, and leave the latter to the stupidity of some, the roguery of others of his disciples. Of this band of dupes and imposters, Paul was the great Coryphaeus, and first corrupter of the doctrines of Jesus.

—Thomas Jefferson, letter to William Short, 1820. From George Seldes, ed., The Great Quotations, Secaucus, New Jersey: Citadel Press, 1983, p. 364.

In 1820 as he described his plans for the University of Virginia to his former private secretary, William Short, Jefferson acknowledged that his plan for the first truly secular university would have opposition: weak opposition (in his view) from the College of William and Mary, but strong opposition from “the priests of the different religious sects, to whose spells on the human mind its improvement is ominous.”

—Edwin S. Gaustad, Faith of Our Fathers: Religion and the New Nation, San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1987, p. 48. The letter to Short was dated 13 April 1820.

Jefferson bemoaned the pattern of church life that gave the unenlightened and bigoted clergy “stated and privileged days to collect and catechize us, opportunities of delivering their oracles to the people in mass, and of moulding their minds as wax in the hollow of their hands.” Despite this enormous advantage, however, Virginians are liberal enough, reasonable enough, to “give fair play” to a university [the University of Virginia] set free from dogmatisms and fixed ideas.

—Edwin S. Gaustad, Faith of Our Fathers: Religion and the New Nation, San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1987, p. 48.

This institution [the University of Virginia] will be based on the illimitable freedom of the human mind. For here we are not afraid to follow truth wherever it may lead, nor to tolerate error so long as reason is free to combat it.

—Thomas Jefferson, to prospective teachers, University of Virginia; from George Seldes, ed., The Great Quotations, Secaucus, New Jersey: Citadel Press, 1983, p. 364.

If the freedom of religion, guaranteed to us by law in theory, can ever rise in practice under the overbearing inquisition of public opinion, [then and only then will truth] prevail over fanaticism.

—Thomas Jefferson, as quoted by Edwin S. Gaustad, Faith of Our Fathers: Religion and the New Nation, San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1987, p. 49. Jefferson’s words are, according to Gaustad, from his letter to Jared Sparks, 4 November 1820.

And the day will come when the mystical generation of Jesus, by the supreme being as his father in the womb of a virgin, will be classed with the fable of the generation of Minerva in the brain of Jupiter.… But we may hope that the dawn of reason and freedom of thought in these United States will do away [with] all this artificial scaffolding.

—Thomas Jefferson, letter to John Adams, 11 April 1823, as quoted by E. S. Gaustad, “Religion,” in Merrill D. Peterson, ed., Thomas Jefferson: A Reference Biography, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1986, p. 287.

…Jefferson expressed himself strongly on that larger apocalypse, the Book of Revelation, in a letter to Alexander Smyth of 17 January 1825: it is “merely the ravings of a maniac, no more worthy, nor capable of explanation than the incoherences of our own nightly dreams.” Apocalyptic writing deserved no com-mentary, for “what has no meaning admits no explanation”; therefore, apocalyptic prophecies associated with Jesus deserved and would receive no attention from Jefferson in his Life and Morals of Jesus.

—E. S. Gaustad, “Religion,” in Merrill D. Peterson, ed., Thomas Jefferson: A Reference Biography, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1986, p. 287.

…our fellow citizens, after half a century of experience and prosperity, continue to approve the choice we made. May it be to the world, what I believe it will be, (to some parts sooner, to others later, but finally to all,) the signal of arousing men to burst the chains under which monkish ignorance and superstition had persuaded them to bind themselves, and to assume the blessings and security of self-government. That form which we have substituted, restores the free right to the unbounded exercise of reason and freedom of opinion. All eyes are opened, or opening, to the rights of man. The general spread of the light of science has already laid open to every view the palpable truth, that the mass of mankind has not been born with saddles on their backs, nor a favored few booted and spurred, ready to ride them legitimately, by the grace of God. These are grounds of hope for others. For ourselves, let the annual return of this day [Fourth of July] forever refresh our recollections of these rights, and an undiminished devotion to them.…

—Thomas Jefferson, letter to Roger C. Weightman, June 24, 1826 [Jefferson’s last letter, dated ten days before he died]; from Adrienne Koch, ed., The American Enlightenment: The Shaping of the American Experiment and a Free Society, New York: George Braziller, 1965, p. 372.

Jefferson wrote voluminously to prove that Christianity was not part of the law of the land and that religion or irreligion was purely a private matter, not cognizable by the state.

—Leonard W. Levy, Treason Against God: A History of the Offense of Blasphemy, New York: Schocken Books, 1981, p. 335.

So much is Jefferson identified in the American mind with his battle for political liberty that it is difficult to entertain the possibility that he felt even more strongly about religious liberty. If the letters and activities of his post presidential years can be taken as a fair guide, however, he maintained an unrelenting vigilance with respect to freedom in religion, and an unrelenting, perhaps even unforgiving, distrust of all those who would seek in any way to mitigate or limit or nullify that freedom.

—Edwin S. Gaustad, Faith of Our Fathers: Religion and the New Nation, San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1987, pp. 46-47.

…Jefferson, who as a careful historian had made a study of the origin of the maxim [that the common law is inextricably linked with Christianity], challenged such an assertion. He noted that “the common law existed while the Anglo-Saxons were yet pagans, at a time when they had never yet heard the name of Christ pronounced or that such a character existed…. What a conspiracy this, between Church and State.”

—Leo Pfeffer, Religion, State, and the Burger Court, Buffalo, New York: Prometheus Books, 1984, p. 121.)

…The most revealing writings concerned the commonly repeated maxim that Christianity was part of the common law. In two posthumously published writings, an appendix to his Reports of Cases Determined in the General Court and a letter to Major John Cartwright, Thomas Jefferson took issue with the maxim. He traced the erroneous interpretation to a seventeenth-century law commentator who, Jefferson argued, misinterpreted a fifteenth-century precedent. He then traced the error forward to his favorite bête noire, Lord Mansfield, who wrote that “the essential principles of revealed religion are part of the common law.” Jefferson responded with a classic, positivistic critique: Mansfield “leaves us at our peril to find out what, in the opinion of the judge, and according to the measures of his foot or his faith, are those essential principles of revealed religion, obligatory on us as part of the common law.”

—Daniel R. Ernst, “Church-State Issues and the Law: 1607-1870” in John F. Wilson.;, ed., Church and State in America: A Bibliographic Guide. The Colonial and Early National Periods, New York: Greenwood Press, 1986, p. 337. Ernst gives his source as Thomas Jefferson, “Whether Christianity is Part of the Common Law?”

It was what he did not like in religion that gave impetus to Jefferson’s activity in that troublesome and often bloody arena. He did not like dogmatism, obscurantism, blind obedience, or any interference with the free exercise of the mind. Moreover, he did not like the tendency of religion to confuse truth with power, special insight with special privilege, and the duty to maintain with the right to persecute the dissenter. Ecclesiastical despotism was as reprehensible as despotism of the political sort, even when it justified itself, as it often did, in the name of doing good. This had been sufficiently evident in his native Virginia to give Jefferson every stimulus he needed to see that independence must be carried over into the realm of religion.

—E. S. Gaustad, “Religion,” in Merrill D. Peterson, ed., Thomas Jefferson: A Reference Biography, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1986, p. 279.

…If this [extending religion’s influence on the basis of “reason alone”] is the path chosen by Omnipotence and Infallibility, what sense can there possibly be in “fallible and uninspired men…setting up their own opinions and modes of thinking as the only true and infallible”? No sense at all, argued Jefferson, who found compulsion in religion to be irrational, impious, and tyrannical. If such compulsion is bad for the vulnerable citizen, its consequences are no more wholesome for the church: “It tends also to corrupt the principles of that very religion it is meant to encourage, by bribing, with a monopoly of worldly honours and emoluments, those who will externally profess and conform to it.”

—E. S. Gaustad, “Religion,” in Merrill D. Peterson, ed., Thomas Jefferson: A Reference Biography, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1986, p. 280.

A final example of Jefferson’s separationism may be drawn from his founding of the University of Virginia in the last years of his life. Prepared to transform the College of William and Mary into the principal university of the state, Jefferson would do so only if the college divested itself of all ties with sectarian religion—that is, with its old Anglicanism now represented by the Protestant Episcopal Church. The college declined to make that break with its past, and Jefferson proceeded with plans for his own university well to the west of Anglican-dominated tidewater Virginia. In Charlottesville this new school (“broad & liberal & modern,” as Jefferson envisioned it in a letter to [Joseph] Priestly of 18 January 1800) opened in 1825 with professorships in languages and law, natural and moral philosophy, history and mathematics, but not in divinity. In Jefferson’s view, as reported in Robert Healey’s Jefferson on Religion in Public Education, not only did Virginia’s laws prohibit such favoritism (for divinity or theology was inevitably sectarian), but high-quality education was not well served by those who preferred mystery to morals and divisive dogma to the unities of science. Too great a devotion to doctrine can drive men mad; if it does not have that tragic effect, it at least guarantees that a man’s education will be mediocre. What is really significant in religion, its moral content, would be taught at the University of Virginia, but in philosophy, not divinity. If Almighty God has made the mind free, one of the ways to keep it free is to protect young minds from the clouded convolutions of theologians. Jefferson wanted education separated from religion because of his own conclusions concerning the nature of religion, its strengths and its weaknesses, its dark past and its possibly brighter future.

—E. S. Gaustad, “Religion,” in Merrill D. Peterson, ed., Thomas Jefferson: A Reference Biography, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1986, pp. 282-283.

Moving well beyond the traditional deistic triad of God, freedom, and immortality, Jefferson revealed his strongest feelings and convictions with regard to the ecclesiastics. On two counts he found them critically deficient. In the realm of politics and power, they were tyrannical; in the realm of theology and truth, they were perverse. Jefferson’s strongest language is reserved for those clergy who, as he said in a letter to Moses Robinson of 23 March 1801, “had got a smell of union between church and state” and would impede the advance of liberty and science. Such clergy, whether in America or abroad, have so adulterated religion that it has become “a mere contrivance to filch wealth and power to themselves” and a means of grasping “impious heresies, in order to force them down [men’s] throats” (letter to Samuel Kercheval, 19 January 1810). In his old age, Jefferson softened his invective not one whit: “The Presbyterian clergy are the loudest, the most intolerant of all sects, the most tyrannical and ambitious, ready at the word of the lawgiver, if such a word could be obtained, to put the torch to the pile, and to rekindle in this virgin hemisphere, the flames in which their oracle Calvin consumed the poor Servetus, because he could not find in his Euclid the proposition which has demonstrated that three are one, and one is three.” And if they cannot revive the holy inquisition of the Middle Ages, they will seek to mobilize the inquisition of public opinion, “that lord of the Universe” (letter to William Short, 13 April 1820). Jefferson, the enemy of all arbitrary and capricious power, found that which was clothed in the ceremonial garb of religion to be particularly despicable.

Even more disturbing to Jefferson was the priestly perversion of simple truths. If “in this virgin hemisphere” it was no longer possible to burn men’s bodies, it was still possible to stunt their minds. In the “revolution of 1800” that saw Jefferson’s election to the presidency, the candidate wrote to his good friend Rush that while his views would please deists and rational Christians, they would never please that “irritable tribe of priests” who still hoped for government sanction and support. Nor would his election please them, “especially the Episcopalians and the Congregationalists.” They fear that I will oppose their schemes of establishment. “And they believe rightly: for I have sworn upon the altar of God, eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man” (23 September 1800).

It was this aspect of establishment that Jefferson most dreaded and most relentlessly opposed—not just the power, profit, and corruption that invariably accompanied state-sanctioned ecclesiasticism but the theological distortion and intellectual absurdity that passed for reason and good sense. We must not be held captive to “the Platonic mysticisms” or to the “gossamer fabrics of factitious religion.” Nor must we ever again be required to confess that which mankind did not and could not comprehend, “for I suppose belief to be the assent of the mind to an intelligible proposition” (letter to John Adams, 22 August 1813).

—E. S. Gaustad, “Religion,” in Merrill D. Peterson, ed., Thomas Jefferson: A Reference Biography, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1986, p. 291.)

To conclude this discussion of the religious clauses of the First Amendment, let’s talk some more about Thomas Jefferson and his “wall.” Some TV preachers, as well as writers, politicians, and, worst of all, Supreme Court Justice William Rehnquist, have sought to pull down the wall by disparaging Jefferson’s influence on the First Amendment. A popular bit of historical revisionism that floats around these days goes something like this: Jefferson served as ambassador to France during the writing of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. He had no hand in their preparation and passage because he was out of the country. Therefore, his metaphor about the “wall of separation” is misplaced and ill-informed because he was living in France and was out of touch.

Tommyrot! Thomas Jefferson was James Madison’s mentor. Madison as the chief architect of both the Constitution and the Bill of Rights drew heavily from Jefferson’s ideas and kept in regular contact with his fellow Virginian even though the latter lived in France. Volumes of correspondence exist between the two men as they discussed the day’s crucial events. Jefferson understood that the First Amendment created a separation between church and state because he, more than most of the Founders, gave form and substance to the nation’s understanding of how the two institutions should best relate in the new nation. Some politicians, lawyers, and preachers subject us to mental cruelty when they disparage Jefferson’s interpretation simply because he lived in France during the years of the Constitution’s framing.

—Robert L. Maddox, Baptist minister and speech writer and religious liaison for President Jimmy Carter, Separation of Church and State: Guarantor of Religious Freedom, New York: Crossroad Publishing, 1987, pp. 67-68.

I take to heart Jefferson’s aspiration that the idea of church-state separation “germinate and take root among [the American people’s] political tenets.”

—Kenneth S. Saladin, “Municipal Church-State Litigation and the Issue of Standing,” in the “Church and State” issue of National Forum: The Phi Kappa Phi Journal, Winter, 1988, p. 23.

Jefferson passionately hated Calvinism and the priestcraft and believed that voluntarism would undermine the power of the churches, priests, and superstitious creeds and would free American minds for a natural theology without ministers or churches; he denied flatly that America was or should be a Christian nation.

—William G. McLoughlin, Soul Liberty: The Baptists’ Struggle in New England, 1630-1833, Hanover and London: Brown University Press, University Press of New England, 1990, p. 259.)

More—much more—on and by others—Washington, Madison, etc.— in the next installments.

Note: Anyone may copy and publish what I or my guests write, provided proper credit is given, that it’s not done for commercial purposes, that I am notified of the copying (you can just leave a comment saying where the copy is being published), and provided that what any of us write is not quoted out of context or distorted.

Thanks for reading Letters to a Free Country! Subscribe for free (always) to receive new posts and support my (our) work.